Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings show his body measurements.

What would you do if you had to draw a person and were asked to make the drawing perfectly proportioned?

This has been the challenge artists of all kinds have faced since humans first began painting cave walls more than 40,000 years ago: finding a simple set of rules that would help them depict the human figure as realistically as possible.

The rules—called the artistic canon—that are taught in art schools today are based on the experiments and measurements made by hundreds of visionaries throughout history.

For example, Loomis, one of the most common methods of teaching drawing, uses lines to divide the body into eight equal parts, all the same size as the head. This means that according to this method, “the idealized human body is eight heads high, the torso is three heads, and the legs are four.”

With that, you could start drawing your proportionally correct person. Just eight ovals, one on top of the other.

Artists today learn methods based on the observations of great artists of antiquity.

But how did you come up with the idea of using lines to divide and geometric figures to represent the body? And who was most advanced in defining the perfect measurements?

At BBC Mundo, we take a journey through art history to meet the sculptors, painters and architects (yes, architects) who, through their visual acuity and limitless ingenuity (along with lots of trial and error), have achieved the most perfect drawing ever. About ourselves.

Here we select four earlier attempts to discover the ideal proportions of the body before Leonardo da Vinci arrived at a theory that is still lauded today.

1. The 18 line grid

The ancient Egyptians used a grid to maintain the proportions of their figures.

After years of studying the works of ancient Egypt, Danish Egyptologist Erik Iversen published a book in 1955 that would change people’s perception of the art of this ancient civilization.

Continue reading the story

During his investigations, Iversen found traces of a grid of 18 horizontal and 18 vertical lines on which some human images were depicted. They all agreed that the first line was on the sole of the character’s foot and the last on the line where the hair begins.

Iversen took these measurements and compared them to various statues of the time. He realized that the ancient Egyptians used these measurements to maintain the correct proportions of the human figure in their depictions, ie they had the first artistic canon known to us.

The study of these proportions, which Iversen compiled in Canon and Proportions in Egyptian Art, is an area that continues to this day, given the few records that exist.

Iversen realized that the statues followed the ratio of 18 lines to the beginning of the hair. It is believed that this is due to the high crowns of the time.

But the discoveries made in recent years are very remarkable: art historian Gay Robbins says in her book Proportion and Style in Ancient Egypt that the original 18-line grid may have evolved into a more accurate grid. , from 19, when art developed within the same empire.

2. Polykleitos and the little finger

Between 450 and 415 BC a Greek sculptor was named polykleitos He began making beautiful bronze statues of young athletes, but with certain details that seemed to give them more credibility.

Polykleitos had the idea that the body in a sculpture had to be represented as a system of forces and counterforces – tense and relaxed parts of the body – in order to give it a dynamic impression.

Some authors suggest that Polykletos’s ideas were influenced by those of Pythagoras by Samos and his followers, who believed that everything in the natural world followed one basic language: that of numbers.

Doryphorus of Polykletos is also known as a canon. It is believed that Polykletos based his canon of proportions on the work on this bronze statue, of which only reproductions survive.

However, the art professor is at the University of Virginia Francesca Fiorani He told BBC Mundo that Policleto was ingenious enough not to fall into arbitrary measures that wouldn’t work for different types of bodies.

“The Polykleitos canon is not a mathematical rule, but a relational rule,” he says, referring to the sculptor’s system in which he took parts of the body, such as the phalanx of the little finger, as a reference index for measuring the entire body.

His system was so influential in antiquity that it resulted in a work by the famous first-century Greek physician Galen refers to the canon of Polykleitos: “Beauty lies in the symmetry of the parts.” [del cuerpo]such as finger to finger […] as it is written in the canon of Polykleitos”.

3. Vitruvius and the navel

For Vitruvio, the perfect proportion of the human body should be the basis of architectural structures.

Directly influenced by the concepts of Greek beauty, the concept of symmetry began to be transferred to other disciplines, including architecture, in Rome.

A Roman soldier and architect named vitruvian He made it his mission to focus on these Pythagorean ideas of mathematics and wrote a ten-book treatise (of architecture), in which he explains what an architect does, what training he needs, what types of buildings and structures he is responsible for, where the principles and ideas for building come from and, above all, how important it is to imitate nature as a building Starting point for the design.

The idea of proportionality is central to the Vitruvian treatise De Architectura.

Vitruvius, who like Polycletos was influenced by the Pythagoreans, in his third book on architecture, suggests that the design of the perfect temple should be guided by the proportions of the human body, writing the following: “The navel is at the center of the human body and.” When a man lies face up with his hands and feet outstretched, a circle can be described from the navel as the center, touching his fingers and toes.

“The human body is not just limited to a circle, it can also be seen in a painting.”

The intention was to design a building based on these two basic geometric figures, the square and the circle, while maintaining the correct proportions of the human body.

To achieve this, Vitruvius gives the indications for a symmetrical body: “The length of a foot is one-sixth the height of the body. The forearm a quarter. The width of the chest a quarter.”

The Renaissance, like the ancient Greeks and Romans, believed in the relationship between the “microcosm of man and the macrocosm of the earth,” as seen in this illustration from the Renaissance writings of Vitruvius.

of architecture It survived thanks to copies kept in Charlemagne’s private library, for example, and was only rediscovered more than 1,400 years later, in the Renaissance.

4. The man in the middle

In 1486, Giovanni Sulpizio da Veroli, a humanist interested in the classics of the Graeco-Roman world, gained access to the Vitruvian manuscript and published it for the first time of architecture.

Thanks to the printing press, works that were previously only available to the clergy entered the public domain. And with the Renaissance’s interest in the Graeco-Roman classics, Vitruvius’s treatise became indispensable to the architects of the time.

Famous names like Philip Brunelleschi, who designed the dome of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, studied the work of Vitruvius and adapted elements from his canon. EITHER Francesco di Giorgio and Leonardo da Vinci.

The imposing dome of Florence Cathedral, the work of Filipo Brunellechi, a scholar of classics such as Vitruvius.

“What made Vitruvio’s work appealing to Leonardo and Francesco was that it gave concrete expression to the analogy inherited from Plato and the ancients, which had become a crucial metaphor for Renaissance humanism,” writes Walter Isaacson in his biography Leonardo da Vinci: “The relationship between the microcosm of man and the macrocosm of the earth”.

Francesco di Giorgio, one of the most renowned architects of his time and a great friend of Leonardo, says in his writings: “All the arts and all the rules of the world derive from a well-formed and well-proportioned human body.” A thought very similar to that of Vitruvius is.

Various Renaissance architects, including Giacomo Andrea and Francesco di Giorgio, attempted to follow the Vitruvian rules, but it had to be someone well versed in all fields, interpreting and executing them in a way that would mark the history of art.

Finally Leonardo

Unlike the group of architects with whom he spent time at this stage in his life, Leonardo saw something more interesting in the work of Vitruvius. “Leonardo is interested in the human body,” Professor Francesca Fiorani told BBC Mundo. Specifically: “The human body in motion.”

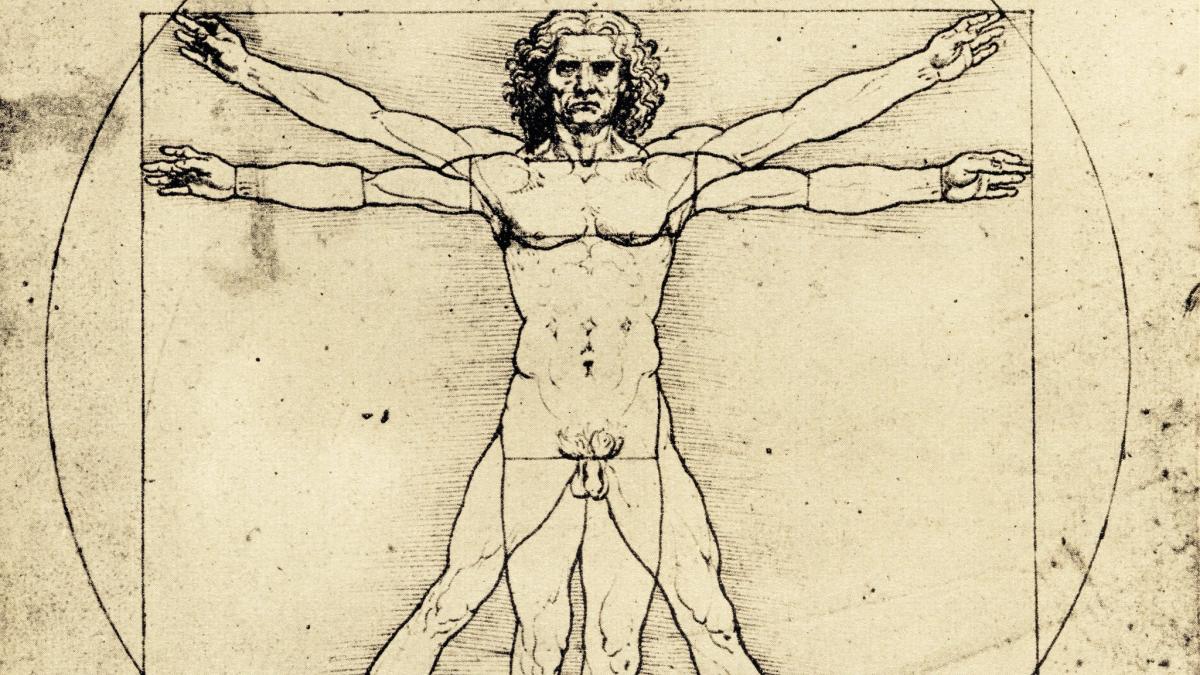

The Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing of the Vitruvian Man is currently kept in a dark room in the Accademia Gallery in Venice to prevent deterioration.

Leonardo carried it with him until his death and it has become one of the most iconic images in western culture.

Walter Isaacson describes it in his book as “a carefully executed drawing, unlike those of his contemporaries”.

“In one of his notes below the drawing, Leonardo describes other aspects of positioning: ‘When you part your legs so that your head is bowed one fourteenth of your height and you raise your hands so that your fingers are stretched out.’ Touch the line of your head and be aware that the center of your outstretched arms will be your navel.

Therein lies the difference between Leonardo’s thinking and that of his contemporaries, explains Fiorani, who presents a study of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian man.

“Her concern was not so much the architecture as the human body and the human body in motion,” the scientist explains to BBC Mundo. “It draws a man with his arms and legs open inside the circle, but then it draws the same man — not a different one — with his legs closed and his arms open, but at different angles.”

“Since the navel of the two male figures is the center of the body and the circle, it conforms to the rules, but the center of the painting is the genitals. What it does is give you the feeling of movement,” says Fiorani.

Through his detailed observations, Leonardo designed his own measurements.

Isaacson relates that for his drawing Leonardo ignored the measurements of the body provided by Vitruvius – although he acknowledged the measurements in the drawing to Vitruvio – and used those that he could identify himself.

Experts agree that the secret of Leonardo’s genius was that he used direct observation and experiment, rather than relying on rules established by others, and that he was inspired by his detailed anatomical studies of cadavers – images of which remain in medical corpses to this day books – this corrected some errors made by the Roman architect in his original measurements.

This is reflected, according to Isaacson, in the fact that less than half of the 22 measurements Leonardo used on Vitruvian man matched those given by Vitruvius in his original text.

“The length of the outstretched arms is the height of a man,” reads the footnotes of what the Briton Martin Kemp, art historian and Leonardo expert, has called “the most famous drawing in history.”

Leonardo’s notebooks show the diversity of his interests. His anatomical studies consisted of dissecting cadavers and making notes that are used in some medical texts to this day.

In a 2020 study conducted by experts at the West Point Military Academy in the United States, they used the measurements of nearly 65,000 people between the ages of 17 and 21 and found that the data collected by Da Vinci was embodied in his famous drawing of the year 1492- are fascinatingly close to reality.

Diana Thomas, a West Point mathematician, said: “Despite different samples and methods of calculation, Da Vinci’s ideal human body and its proportions resembled those determined by contemporary methods of measurement.”

After the Renaissance, Western art became less concerned with depicting reality as it is perceived and began to experiment with the abstract, with the things we perceive but don’t have a natural visual representation, and with this, interest in realism faded into the background.

Modern methods – like the Loomis we mentioned at the beginning – are simplified versions of these rules, which Da Vinci expressed in a drawing that seeks to reflect the geometric perfection of the human body and its relationship to the geometric perfection it represents the Pythagoreans saw in the cosmos.

But perhaps by following Leonardo’s example and looking by our own standards, we can find something that the genius himself did not see and continue to contribute to the development of something as deeply human as art.

Just as the Renaissance genius would have done in his hundreds of notebooks, you now face a new challenge: “Draw a proportionately correct human body.”

YOU MAY ALSO BE INTERESTED | ON VIDEO

France exhibits Leonardo da Vinci’s last work

![]()