Towards the end of his life, with his memory destroyed, Gabriel García Márquez struggled to complete a novel about the secret sex life of a middle-aged married woman. He tried at least five versions and tinkered with the text for years, shortening sentences, scribbling in the margins, changing adjectives and dictating notes to his assistant. Finally he gave up and issued a final, damning verdict.

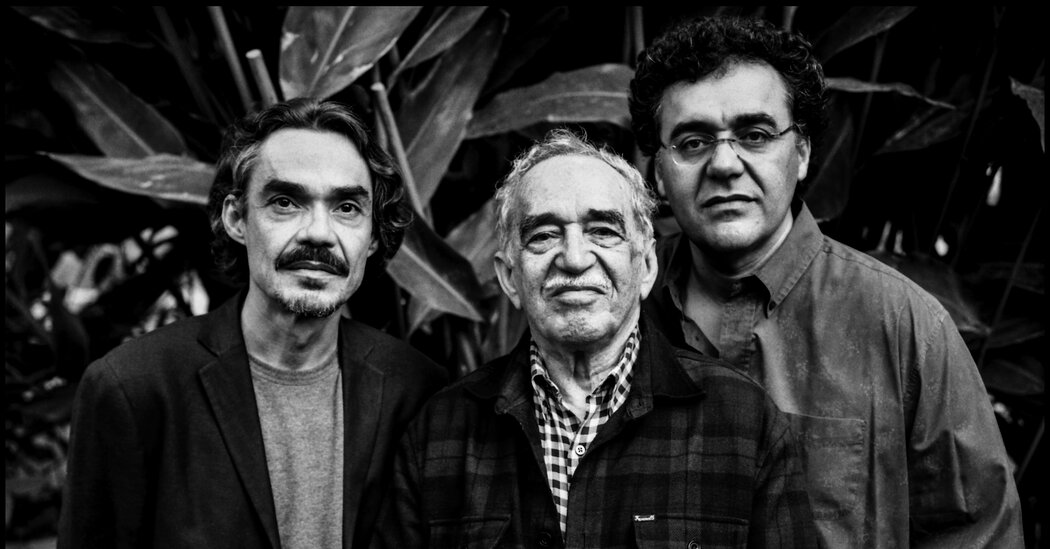

“He told me directly that the novel had to be destroyed,” said Gonzalo García Barcha, the author’s younger son.

When García Márquez died in 2014, several drafts, notes, and chapter fragments of the novel were preserved in his archives at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. The story remained there, spread across 769 pages, largely unread and forgotten – until García Márquez's sons decided to defy their father's wishes.

Now, a decade after his death, his final novel, Until August, will be released this month and will be published in nearly 30 countries worldwide. The story focuses on a woman named Ana Magdalena Bach, who travels to a Caribbean island every August to visit her mother's grave. On these dark pilgrimages, briefly freed from her husband and family, she always finds a new lover.

The novel adds an unexpected coda to the life and work of García Márquez, a literary giant and Nobel Prize winner, and is likely to raise questions about how estates and publishers should handle posthumous publications that contradict a writer's instructions.

Literary history is littered with examples of famous works that would not have existed if executors and heirs had not ignored the authors' wishes.

According to classical tradition, on his deathbed the poet Virgil demanded that the manuscript of his epic poem “The Aeneid” be destroyed. When Franz Kafka became seriously ill with tuberculosis, he instructed his friend and executor Max Brod to burn his entire work. Brod betrayed him and delivered surrealist masterpieces such as The Trial, The Castle and America. Vladimir Nabokov ordered his family to destroy his last novel, The Original Laura, but more than 30 years after the author's death, his son published the unfinished text that Nabokov had sketched on index cards.

In some posthumous works, the author's intentions for the text were unclear, leading scholars and readers to question how complete it was and how much leeway the editors gave themselves with the manuscript. Occasionally, estates and heirs are criticized for damaging an author's legacy by publishing inferior or unfinished works in order to squeeze every last bit of intellectual property out of a literary brand name.

For García Márquez's sons, the question of what to do with “Until August” was complicated by their father's conflicting assessments. He worked intensively on the manuscript for a while and eventually sent a draft to his literary agent. It wasn't until he suffered severe memory loss due to dementia that he decided it wasn't good enough.

By 2012, he could no longer recognize even close friends and family – one of the few exceptions was his wife, Mercedes Barcha, his sons said. He found it difficult to continue a conversation. Occasionally he would pick up one of his books and read it without recognizing the prose as his own.

He confessed to his family that he felt helpless as an artist without his memory, which was his primary source material. Without memory, “there is nothing,” he told them. In this broken state, he began to doubt the quality of his novel.

“Gabo lost the ability to judge the book,” said Rodrigo García, the eldest of his two sons. “He probably wasn’t even able to follow the plot anymore.”

When his sons reread “Until August” years after his death, they felt that García Márquez may have judged himself too harshly. “It was a lot better than we remembered,” García said.

His sons admit that the book is not one of García Márquez's masterpieces and fear that some might dismiss its publication as a cynical attempt to make more money from their father's inheritance.

“We were obviously afraid of being seen as just greedy,” García said.

In contrast to his sprawling, lush works of magical realism — epics like “Love in the Time of Cholera” and “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” which sold some 50 million copies — “Until August” is modest in scope. The English language edition, published March 12th and translated by Anne McLean, is only 107 pages long.

The brothers argue that it is a valuable addition to García Márquez's oeuvre, also because it reveals a new side of him. For the first time, he focused a narrative on a female protagonist and told an intimate story about a woman in her late 40s who, after almost 30 years of marriage, begins to seek freedom and self-realization through illicit romantic relationships.

Still, some readers and critics may question her decision to publish a work that García Márquez himself considered incomplete, perhaps adding a disappointing footnote to a tremendous legacy.

In his native Colombia, where García Márquez's face appears on the currency and anticipation for the book is high, many in literary circles are excited about anything new from García Márquez, no matter how unpolished it may be. Still, some are concerned about the way the novel is being sold.

“They are not offering it to you as a manuscript, as an unfinished work, they are offering you the last novel by García Márquez,” said Colombian writer and journalist Juan Mosquera. “I don’t believe in the greatness we give him. I think it is what it is – a great commercial moment for the García Márquez signature and brand.”

Colombian writer Héctor Abad said he was initially skeptical about the publication but changed his mind when he read an advance copy.

“I was afraid that it might be an act of commercial opportunism, and no, the opposite is true,” Abad, who will appear at an event celebrating the novel in Barcelona, said in an email. “All the virtues that made the best García Márquez great are also present here.”

There is no doubt that at some point García Márquez felt that the novel was worth publishing. In 1999 he read passages at a public appearance with the writer José Saramago in Madrid. Excerpts from the story were later published in Spain's leading newspaper, El País, and the New Yorker. He put the project aside to finish his memoirs and published another novel, Memories of My Melancholy Whores, which received mixed reviews. In 2003 he began working intensively on it again and a year later he sent the manuscript to his agent, the late Carmen Balcells.

In the summer of 2010, Balcells called Cristóbal Pera, an editor who had worked with García Márquez on his memoirs. She said that García Márquez, who was then in his 80s, was trying to finish a novel and asked Pera to help him. García Márquez was very reserved about his work in progress, but a few months later he allowed Pera to read a few chapters of the novel and seemed enthusiastic about it, Pera recalled. About a year later, as his memory failed, the author struggled to understand the narrative but continued to make notes in the margins of the manuscript.

“It was therapeutic for him because he was still able to do something with pen and paper,” Pera said. “But he didn’t want to finish.”

When Pera gently urged García Márquez to publish the book, the author was strongly against it. “He said, at this point in my life, I don’t need to publish anything anymore,” Pera recalls.

After his death at age 87, various versions of “Until August” were preserved in the Ransom Center archives.

Two years ago, García Márquez's sons decided to revisit the text. The novel is messy in places, with some contradictions and repetitions, they said, but it feels complete, if unpolished. There were flashes of his lyricism, like a scene in which Ana, about to confess her infidelity at her mother's grave, “balls her heart into a fist.”

When the brothers decided to publish the novel, they were faced with a conundrum. García Márquez had left at least five versions in various stages of completion. But he gave a hint as to which one he preferred.

“One of the folders he kept had 'Gran OK final' written on the front,” García Barcha said.

“That was before he decided it wasn’t okay at all,” his brother added.

When they asked Pera to edit the novel last year, he began work on the July 2004 fifth version – the version labeled “Gran OK final.” He also relied on other versions and on a digital document compiled by García Márquez's assistant, Mónica Alonso, with various annotations and changes that the author wanted to make. Pera was often confronted with competing versions of a sentence or phrase—one typed, one handwritten in the margins.

Pera attempted to correct inconsistencies and contradictions, such as the protagonist's age – García Márquez varied as to whether she was middle-aged or elderly – and the presence or absence of a mustache on one of her lovers.

To create the most coherent version possible, Pera and the brothers established a rule: They would not add a single word that did not come from García Márquez's notes or other versions, they said.

As for the fate of all of García Márquez's other unpublished works, his sons say it is not a problem: there is nothing else. Throughout his life, García Márquez regularly destroyed older versions of published books and unfinished manuscripts because he did not want them to be subject to later scrutiny.

That was one of the reasons they decided to release “Until August,” they said.

“When this book comes out, we will publish all of Gabo’s works,” García Barcha said. “There’s nothing else in the drawer.”

Genevieve Glatsky contributed reporting from Bogota.