Bribes, secret meetings, new testimonies about the collusion between the authorities and drug dealers in Mexico. Genaro García Luna’s trial just ended its most controversial week because of everything that happened and what was said. The latest allegations sparked reactions from former President Felipe Calderón, former PRI governors Roberto Sandoval and Humberto Moreira, and El Universal, one of the country’s best-known newspapers. The Brooklyn court was filled with the testimonies of 25 witnesses who explained in great detail how the criminals roamed with impunity thanks to the payment of dirty money, how the security institutions failed, and how those involved signed a tacit agreement to cover their backs and collect the benefits. The first-person narratives of drug dealers and corrupt officials clashed once again with the versions of those singled out and in denial. Amid the hurricane, prosecutors have struggled to provide tangible evidence to support the allegations and have focused on basing their legal strategy on the testimonies of cooperating witnesses. The last person they are calling to testify will appear next week, almost three weeks ahead of schedule. They also announced it just a few days ago.

Explosive accusations and categorical denials

The New York trial of García Luna has scrutinized the links between organized crime and the authorities. The former public safety minister and former drug kingpin spent three weeks in the dock for siding with and protecting the cartels he promised to fight. “When they talk about everything they do, it’s shocking, it’s even stronger than a thought,” says journalist Ioan Grillo, who has been writing about the violence and crime that plagues the country for more than 20 years. “There’s a feeling of a drug state in Mexico,” he adds.

Édgar Veytia, one of the most anticipated witnesses at the trial, made headlines for stating that during the Calderón government, orders were given to protect the people of Joaquín El Chapo Guzmán from other cartels. The testimony was based on a conversation he allegedly had with then-governor Ney González early in his political career. “I’ve just come from a very important meeting in Mexico City with Felipe Calderón and Genaro García Luna, where they told us that the line was El Chapo,” the convict said, recalling the words he attributed to González. “I have never negotiated or agreed with criminals,” the former president wrote on his social media.

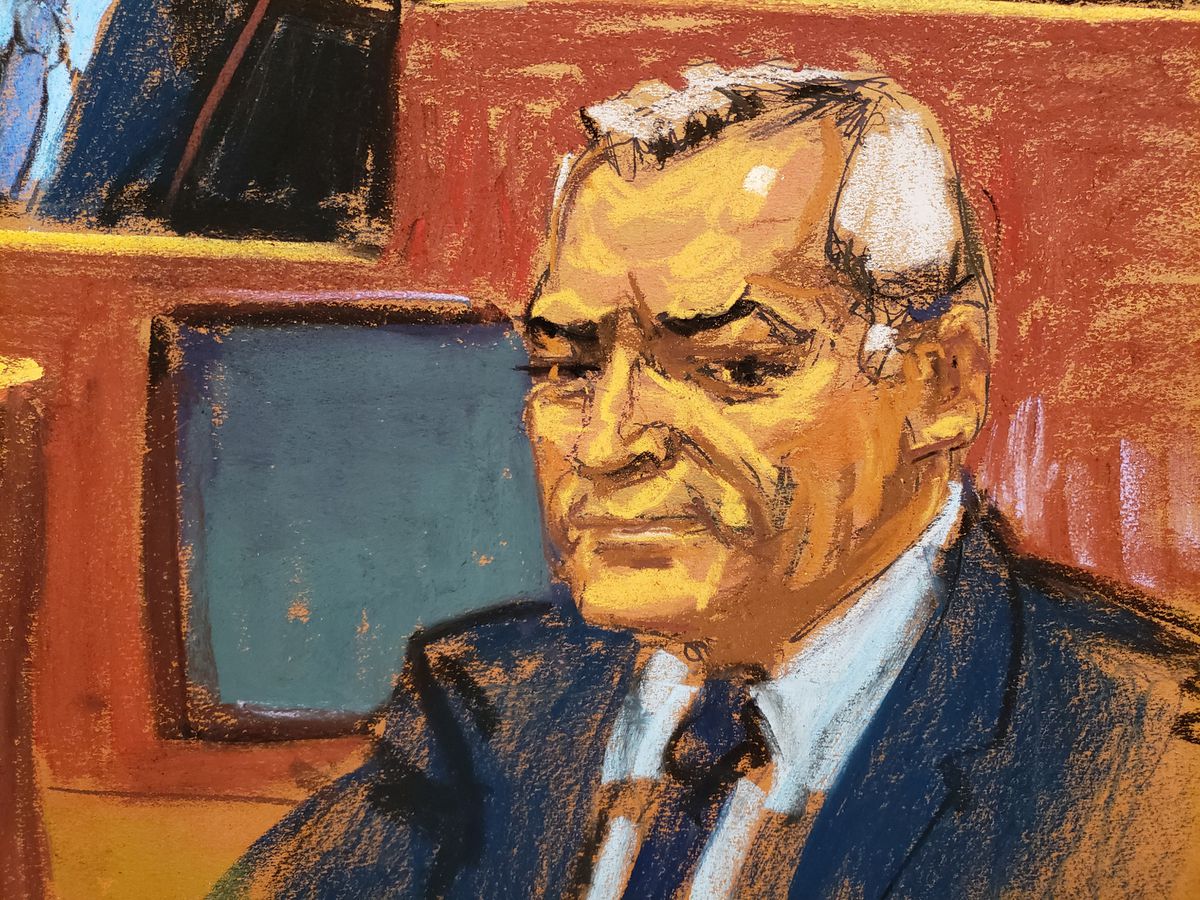

Edgar Veytia declares in the trial of Genaro García Luna in New York on February 7. JANE ROSENBERG (Portal)

Edgar Veytia declares in the trial of Genaro García Luna in New York on February 7. JANE ROSENBERG (Portal)

The statement was explosive, but could not be supported by more solid evidence. In the end, Veytia did not meet with the then President, nor was he present during the alleged investigation. The former Nayarit prosecutor dated Luis Cárdenas Palomino, García Luna’s right-hand man and the main co-defendant in the case. “He told us to support El Chapo,” he said. The witness, sentenced to 20 years in 2019 for links to the drug dealer, also recounted how he put himself in the service of Juan Francisco Patrón Sánchez, aka El H2: he murdered, tortured and protected the local boss. “We didn’t stop them, we gave them information so they could flee and evade justice, we covered up their crimes,” admitted Veytia, visibly humiliated. “I deny and strongly deny that my campaign or my person had any relationship with drug trafficking groups,” said former Gov. Sandoval, his old friend who has been jailed in Mexico since 2021.

dirty money

The bribery reports provided to García Luna are the cornerstone of the case and the basis for the charge against him of having ties to organized crime for 20 years. In addition to the indirect testimony, at least two drug lords testified in court that they were directly involved in making illegal payments to the former officer. Sergio Villarreal Barragán, El Grande, assured that since 2001, when García Luna was head of the Federal Investigation Agency (AFI), created during the administration of Vicente Fox (2000-2006), he received more than a million dollars a month have. . He also described how the sausages were assembled, the packets containing wads of money and how they were delivered in black bags after the AFI director was picked up by cartel members in the parking lot of Perisur, a well-known shopping center south .out of the city. Arturo Beltrán Leyva’s lieutenant even drew a sketch of the safe house where the meetings were held. After joining Calderón’s cabinet, García Luna delegated the collection to the cartels in Cárdenas Palomino, according to El Grande.

Óscar Nava Valencia, aka El Lobo, assured that he paid García Luna at least $10 million. El Lobo, for example, said he paid $3 million for a 15-minute meeting with the former secretary at a Guadalajara car wash. On another occasion, Nava Valencia, leader of the Milenio Cartel and originally a Sinaloa Cartel ally, said he paid $5 million in exchange for the then-Secretary to provide information about a seizure of more than 23 tons of cocaine in Manzanillo im October 2007 revealed the largest drug seizure in the world to date. According to his version, García presented Luna with a document to prove that the DEA was already tracking this shipment and to justify to his Colombian partners that the loss of the goods was not his fault. The capo said it saved him $50 million that the Colombian cartels were demanding.

Óscar Nava Valencia “El Lobo” looks at Garcia Luna from the podium on January 30th. JANE ROSENBERG (Portal)

Óscar Nava Valencia “El Lobo” looks at Garcia Luna from the podium on January 30th. JANE ROSENBERG (Portal)

But the money was distributed to all sorts of civil servants and civil servants. Nava Valencia implicated Guillermo Galván Galván, Calderón’s defense minister. Tirso Martínez El Futbolista spoke of bribing state police commanders and toll booth employees. Veytia said he has judges and journalists on his payroll to “save face” as well as the funds that reach the election campaigns. Raúl Arellano, a former federal police officer, said that the federal police command at Mexico City Airport, as well as those in charge of the main airport terminals, received payments for the transportation of narcotics, money and crime weapons. Israel Ávila, who kept the Beltrán Leyva accounts, confirmed this and added the name of Luis Ángel Cabeza de Vaca, the former security secretary of Morelos, to the list. Cabeza de Vaca was cleared of a drug investigation in 2016.

“We had information that high-ranking officials were taking bribes from the cartels there,” concluded Miguel Madrigal, a DEA agent who spent seven years in Mexico, alluding to a restaurant in one of the United States embassies. Tony Wayne, the ambassador at the time, said Washington had gradually lost confidence in the García Luna federal police force, although he qualified that he had no conclusive information about the former officer’s corrupt actions.

Héctor Javier Villarreal, Coahuila’s former treasurer, stated that García Luna not only received bribes, but paid them. The first former official to speak at the trial said the former secretary paid El Universal 25 million pesos a month to boost his image and that of the Ministry of Public Security. He also assured that the pact came about through the mediation of the then governor Moreira. And he added that the money once came from the Coahuila Treasury Department, although García Luna’s name was not on the bill approved by Villarreal and issued to the jury. The former PRI president denied the allegations and said he had clear differences with the accused. The newspaper claimed it was scored without proof.

False confiscations, assemblies and operations directed by the narco

The seizure of Manzanillo in 2007 was one of the key episodes in the interrogations. In addition to El Lobo’s testimony, El Grande asserted that the cartels prepared counterfeit cocaine with sugar and flour to trade for the drug seized by authorities. Villarreal Barragán assured that this is the destination of the goods seized in the mega-operation in the Mexican Pacific port. “After that, Arturo (Beltrán Leyva) was very happy because he had recovered his cargo with almost no loss,” said the capo without remorse. Adrián Ibáñez, a DEA intelligence agent, also spoke about the seizure and during his testimony, images of the allegedly burned cache were shown. The prosecution’s intention was to cast doubt on the jury that the public was simulating the fight against the cartels and that they were getting away with it in private.

Another issue that attracted attention was the alleged insurgency suffered by García Luna in 2008 at the hands of Arturo Beltrán Leyva’s associates. The incident, which the accused has denied every time in the past, happened in Morelos without the ex-secretary’s escort putting up any resistance, Villarreal Barragán said. “Anything is possible in Mexico, there is a lot of corruption,” El Grande said. Harold Poveda El Conejo, a Colombian drug dealer who became one of Beltrán Leyva’s closest men, said he convinced his former boss not to kill the officer. “By God, how do you want to do that, if we then get into trouble, the government will come with everything,” said El Conejo, who was not an eyewitness to the kidnapping.

Francisco Cañedo answers questions from César de Castro, García Luna’s lawyer, on February 6. JANE ROSENBERG (Portal)

Francisco Cañedo answers questions from César de Castro, García Luna’s lawyer, on February 6. JANE ROSENBERG (Portal)

Francisco Cañedo, a retired ministry agent, said he saw García Luna meet up with La Barbie and Beltrán Leyva on a highway between Tepoztlán and Morelos in October 2008. “I was shaking,” Cañedo admitted. The former police officer asserted that he shared the information with then deputy Layda Sansores, the current governor of Campeche, and released a report of the meeting that he had written for the trade union congress to the media. From the details that Cañedo made, it is concluded that it was not about the kidnapping episode. He said he later interviewed some of the secretary’s bodyguards, who told him they had been disarmed and subdued.

El Grande, El Conejo and El Lobo also gave similar accounts of how the Beltrán Leyva group planned and carried out the capture of Jesús El Rey Zambada, their former ally and later rival. Brutalized by the capture of his brother Alfredo, Arturo Beltrán was determined to bring down El Rey, brother of Ismael El Mayo Zambada, founder of the Sinaloa Cartel. “There were two attempts, in the first we gave the information to the army, but they sold it to the people of El Rey,” El Grande said in another statement about the alleged corruption that runs rampant in law enforcement. In the second case, Villarreal Barragán, a corrupt ex-cop turned drug dealer, donned his official agent’s uniform along with other gunmen. “I was part of the operation,” confirmed Villarreal Barragán. They all declared that those who brought down Zambada were his rivals. For example, El Conejo added that a journalist was paid to break the news of the arrest, although he did not say who.

Poveda, a capo who never had direct contact with García Luna, accused him of being kidnapped and tortured about 18 hours before he was brought before authorities and the media. “Are you the rabbit, son of a bitch? Because you’ve already fooled yourself.” His testimony was the only one brought to the table at the meetings of competent authorities chaired by García Luna, an old allegation in Mexico that has so far been banned from the story that prosecutors have tried to show the jury.

An unexpected twist

“The strategy in general was to have many witnesses with strong and impressive testimonies saying that García Luna is guilty,” Grillo summarizes the plan pursued by prosecutors. Repeating these stories doesn’t seem like a bad tactic in front of the jury, 12 New Yorkers who have no further context about the defendant or the fallout from the case across the border. Over the last three weeks, the panel members have experienced an intensive course on the narco and its stories in the voice of the protagonists. Unlike much of what is written and published in Mexico, the British author does not ignore the impact these statements can have on the jury. And they have the final say on the guilt or innocence of the accused.

Héctor Javier Villarreal, former Treasurer of Coahuila, during interrogation by prosecutors on February 6. JANE ROSENBERG (Portal)

Héctor Javier Villarreal, former Treasurer of Coahuila, during interrogation by prosecutors on February 6. JANE ROSENBERG (Portal)

Almost as controversial as any testimony in the 10 hearings the trial had was the prosecution’s obligation to base the case almost entirely on testimonies from associates. “I thought that in order to go to court against García Luna, against a former official of this level, they had to have a smoking gun,” says the writer, who attended the first phase of the hearings in New York. Grillo refers to what is also known as the “miracle weapon” or decisive and incontrovertible evidence. “It was a disappointment that there wasn’t anything else like recording,” he says. The door to the presentation of more evidence hasn’t closed, but it has narrowed: prosecutors announced this week they are expected to invite their final witness in the coming days. “I don’t think it’s a bad strategy, maybe they feel like they’ve already made their case or realized the judge wants things cut short,” he says. “If García Luna is not convicted, it would be a complete failure of prosecutors and perhaps they would be more cautious about taking on other political cases.”

However, prosecutors’ abrupt decision not to call any more witnesses left a deep impression on a country hoping to proceed with the drug dealer’s testimony that the trial has become. García Luna’s trial was billed as being the great exorcism of the doubts and suspicions that have hung over power in Mexico for the past two decades. However, under these parameters it will be almost impossible to meet these expectations. Because the judge severely restricted the materials and statements reaching the court. Because in the prosecution’s equation for convincing the jury, the interest in the case across the border carries no weight, although it is difficult to accept. Because the costs of these processes, which are carried out 3,000 kilometers from the country’s border, play as a visitor and by the rules of the hosts. “It’s sad that Mexico can’t bring these lawsuits,” says Grillo. The trial will enter a crucial phase starting next week with the conclusion of hearings, the opportunity for closing arguments and a judgment that has not yet been set but is approaching.

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS México newsletter and receive all the important information about current events in this country