The war in Ukraine conjures up a strong historical déjà vu. Though captured in 21st-century fashion through close-up cell phone cameras and high-resolution drone footage, the captured images – of artillery duels and trench warfare – have a distinct last-century vibe.

As with Stalin’s invasion of Finland in the 1939 Winter War, the Russian army is bogged down and bloodied by a much smaller, weaker-armed enemy.

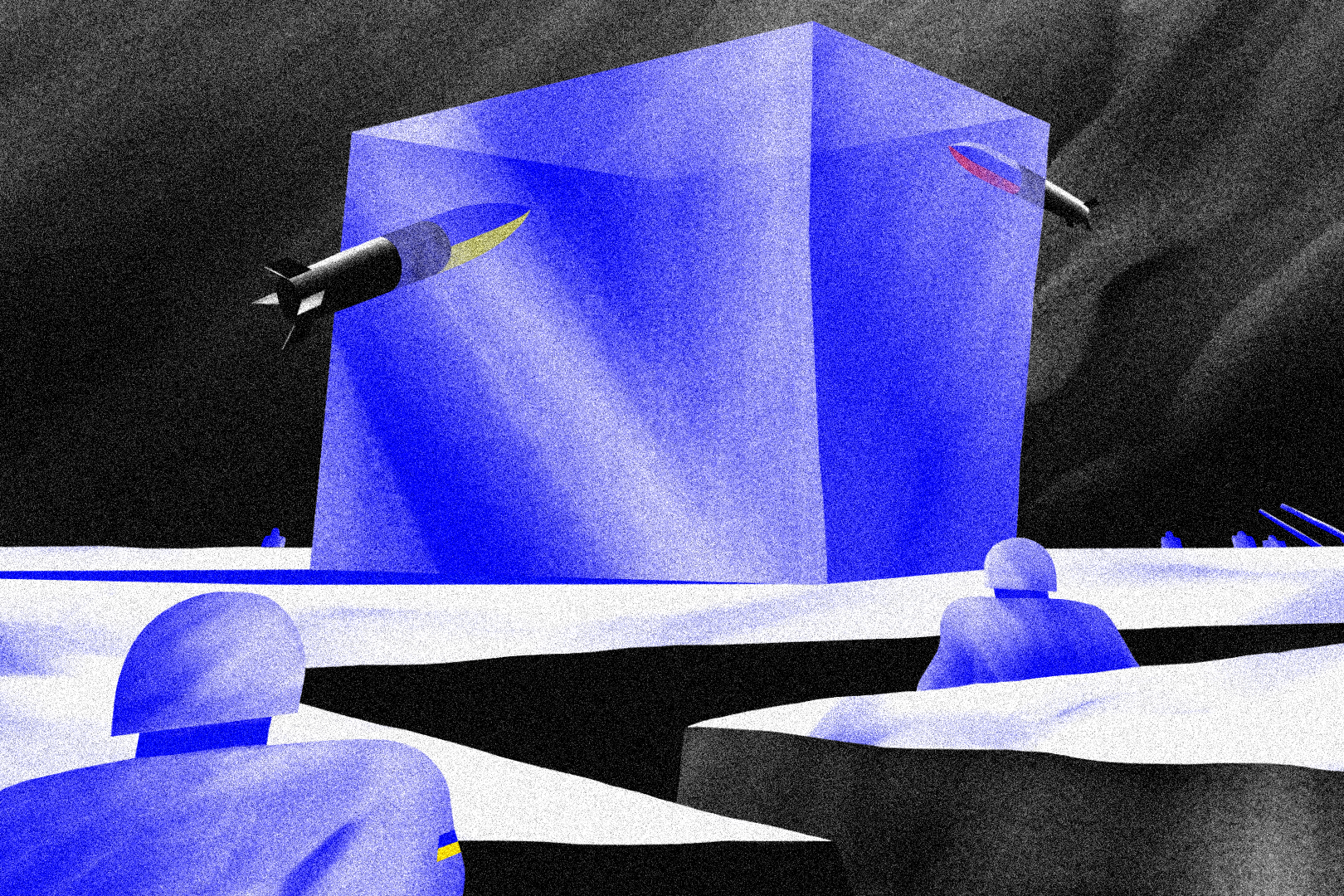

Both sides are now stepping in as Moscow’s “military special operation,” which was only supposed to last a few days, turns into another year of war of attrition. Russia sends waves of recruits and mercenaries into hand-to-hand combat for cities like Bakhmut and Vuhledar.

In the meantime, the western powers have promised Ukraine coveted battle tanks, and there is much talk of a new Russian spring offensive. “Ukraine will never be a victory for Russia. Never,” US President Joe Biden said in Poland last week, a day after a previously unannounced visit to Kiev.

It’s the kind of conflict that Margaret Macmillan, war historian and Professor Emeritus at Oxford University, said: “We didn’t think we’d see it again”. As the bombing of Ukraine enters another year, what do past conflicts, particularly those of the modern era, tell us about how the war might end?

The short answer: While every conflict is unique and tends to defy history, a clear defeat by either side in this war is unlikely, experts said. A more likely scenario is protracted fighting where both sides are exhausted but unwilling to concede defeat, leading to a frozen conflict or an eventual unsteady truce. The probability of a quick end to hostilities is small.

Russian soldiers seen here in Red Square, central Moscow, September 29, 2022, as the square was sealed ahead of a ceremony marking the incorporation of occupied Ukrainian territories into Russia [File: Alexander Nemenov/AFP]

Russia is not Iran or Serbia

The war in Ukraine took on international dimensions when Russian tank columns rolled across the border in February 2022. A conflict in which a major nuclear power and energy exporter violated the sovereignty of a country that is a cornerstone of global food security would never be contained in just two countries.

The US and its allies quickly provided assistance that was vital to Ukraine’s defense capability.

Previous wars, such as the eight-year Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, have also depended on this outside aid. At various points in this conflict, Russia has mirrored Iran’s position and Ukraine’s Iraq’s position in this war – albeit incompletely – said Jeremy Morris, professor of global studies at Aarhus University in Denmark.

This conflict, including between neighbors, was essentially fought over territory and resources. Western weaponry helped Iraq to early battlefield successes against the much larger Iran, which had to resort to more costly tactics such as human wave attacks, in which artillery columns rushed into Iraqi formations and risked heavy casualties in hopes of overwhelming the enemy. “And a proxy war was superimposed,” Morris told Al Jazeera, referring to US support for Iraq to advance its own interests in the Middle East.

There is, of course, one key difference: unlike Ukraine, Iraq started this war.

Yet in Ukraine, Western arms – albeit delivered incrementally and cautiously – were similarly key to halting the Russian advance. In theory, this gives the West leverage over the direction of the war. The West could – as Ukraine has sought – deliver even more sophisticated weapons more quickly, hoping to convince Russia that it cannot win.

Macmillan pointed out that, in fact, sometimes the most important factor in ending open conflict and getting belligerent sides to talk is external pressure.

“Serbia’s war against Kosovo ended because outside powers got involved,” she told Al Jazeera, referring to NATO’s 1999 bombing of Serbia. “Northern Ireland’s civil war ended partly because outside powers stepped in [the US in particular] put a lot of pressure and helped create a framework [for peace]“.

But the calculus in Ukraine does not lend itself to easy solutions from outside.

Unlike Iran and Serbia, Russia is a nuclear power. It has its own war machine and vast reserves of manpower and resources, and Morris believes Russia has a good chance of sustaining the conflict for years to come.

The war and Western sanctions have wreaked havoc on Russia’s society and economy, but Moscow has mitigated the worst effects and is unlikely to remain so weak that it cannot continue the war. Russia’s economy shrank by just over 2 percent last year – far less than expected.

“Russia was already isolated because of its intervention in Donbass in eastern Ukraine in 2014, so it is prepared to be isolated,” Morris said. “Russian living standards could fall precipitously, but they will never get into a position like North Korea – and even North Koreans have endured the conditions they have lived in for more than 50 years.”

Unlike in the case of Serbia, experts do not see a scenario in which the US-led Western alliance would actively attack Russia.

“Serbia was weak compared to NATO,” said Dan Reiter, professor of political science at Emory University and author of How Wars End. “There is no way NATO will act unprovoked against Russia.”

A photo of a Ukrainian soldier is placed on his grave at a cemetery in Kharkiv, Ukraine February 24, 2023, as Ukrainians marked the somber anniversary of the Russian invasion [Vadim Ghirda/AP Photo]

“The Ukrainians will decide”

Likewise, Ukraine’s dependence on its arms gives Western powers a say in planning Kiev’s strategy. In theory, they could threaten to cut aid if they grow weary of the war or if Ukraine, emboldened by its military advances, crosses a threshold that could trigger an escalation unacceptable to the West.

But the idea that Ukraine can be pressured into some kind of peace is “false” and “denies Ukraine’s capacity to act,” said Branislav Slantchev, a professor of politics at the University of California, San Diego and a specialist in war negotiations and how conflicts end .

He said there was little the West could do to prevent Ukrainians from retaking all of their country’s territory currently held by Russia – including parts that Moscow has formally, albeit illegally, annexed.

“Their view is that the West can control the Ukrainians… We can’t really pressure the Ukrainians,” he said.

While the West could warn Kiev that it would cut off arms supplies or financial support if Ukraine insisted on opposing the US or Europe, “that kind of threat is not credible,” Slantchev told Al Jazeera. This is because “the Ukrainians know” that it is in the western interest “not to let them collapse”.

Slantchev said the West knows that any rift in its unity against Russian aggression would only embolden the Kremlin.

“Essentially, once the West made a decision that Ukraine matters… it had to support them to the end, and that means Ukrainians are the ones who will decide when they will stop,” he said.

At present there is little evidence that either side is ready to negotiate.

“For the fight to stop, both sides have to want it,” Slantchev said. “Both sides must expect to benefit more from peace than from fighting on.”

As things stand, despite crushing setbacks on the battlefield, Putin appears poised for a long fight and believes Russia will win. Russia’s allies like China – which was a lukewarm friend to Putin in his war against Ukraine – either could not or would not force him to the negotiating table.

Meanwhile, Russian calls for Ukraine’s demilitarization and neutrality are a “non-starter,” according to Slantchev. Polls in Ukraine show that the public is overwhelmingly opposed to any concessions to Russia.

Emory University’s Reiter cited two main reasons for Ukraine’s lack of appetite for negotiations that would mean accepting the loss of territories. “The war has been so absolutely brutal that they are afraid of what will happen in the territories handed over to Russia,” he said.

The Ukrainians simply don’t trust Moscow either, said Reiter. “Even if they were willing to give up the Donbass region, for example, they cannot trust that this would be the end and that Russia would not come back and ask for more,” he said, referring to the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, in which Russia agreed to respect Ukraine’s borders.

Putin (C) is seen here speaking with Chechen leaders Alu Alkhanov (L) and Ramzan Kadyrov December 12, 2005 in the Chechen capital Grozny. Experts believe the second Chechen war of 1999 shaped Putin’s approach to the region’s attempt to escape Russia [File: Vladimir Rodionov/ITAR-TASS via AFP]

Why Putin isn’t giving in

In many ways, the same man who started the conflict could end it — if he chooses to. The problem, according to experts: He has no incentive to do so.

This is “Putin’s war,” said Oxford professor Macmillan. The Russian President “put his prestige on it, and the more losses, the more difficult it is [it is for him] withdraw”.

Putin’s presidency began with the second Chechen war in 1999, when separatist rebels sought independence from Russia. The war, which ended with the Chechen capital being leveled and Chechen resistance largely crushed, left a lasting mark on Putin’s approach to regions trying to break away from Russian influence, analysts say.

Experts see Putin’s grandiose vision – laid out in his lengthy historical treatises and brutally enforced in places like Chechnya – as what brought him to Ukraine. But they argue that the roots of Putin’s worldview lie in earlier events: the end of the Cold War.

Wars are rarely neatly booked from the first and last shots. For example, there was a continuity between the First and Second World Wars. Certainly a lot has happened in the intervening years that could have changed the direction of what follows. But, according to Macmillan, “The First World War laid the foundations that made the Second possible.” The danger lay in a humiliating peace treaty forced upon defeated Germany.

Experts see a similar connection between the end of the Cold War and the ongoing war in Ukraine.

Putin and the Russian elite have a deep sense of humiliation at the collapse of the Soviet Union. The years that followed were “terrible for many Russians,” Macmillan said. “The country looked weak, its economy was in disarray, there was resentment that the West had not done enough, not offered a Marshall Plan and condescended.”

Maria Popova, associate professor of comparative politics at McGill University, argued that Putin is motivated by a desire to restore Russia’s imperial prestige and correct perceived historical errors.

The Russian ruling elite saw the collapse of the Soviet Union as merely a reconfiguration in which the former Soviet countries “would continue to be together in some way,” Popova told Al Jazeera, while Ukraine saw it as a chance to be fully independent.

For Ukraine, it’s a “civilized divorce,” for Russia it’s a “rewriting of vows,” Popova said. That difference in how the two nations viewed the end of the Cold War is now playing out through blood and bullets.

Ukrainian military fire from a multiple rocket launcher at Russian positions from a snowfield in Kharkiv region, Ukraine, February 25, 2023. Experts fear the conflict could escalate into an eternal war [Vadim Ghirda/AP Photo]

An eternal war?

Something existential is at stake for both sides in this conflict, which makes it all the more insoluble.

Some observers have suggested that continued defeats on the battlefield could lead to Putin’s downfall. Finally, the Russian defeats in the Crimean War in the 19th century and the losses to Japan and Afghanistan in the 20th century triggered profound domestic political changes. A protracted and costly World War I helped initiate the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

But for analysts like Morris, the prospect of Putin being ousted is extremely unlikely – and the chances that whoever replaces him will be less hawkish are even slimmer. “There’s not really an alternative energy source to rally around as long as Putin is healthy and alive,” Morris said.

And this has direct consequences for the future of the war in Ukraine.

“I don’t think this can end as long as Putin is in power,” Slanchev said. “Even if the Ukrainians push the Russians to the borders, I don’t think he will negotiate if he’s still in power.”

Protracted, slow-burning conflicts have helped Russia establish breakaway, pro-Kremlin enclaves in Ukraine (Donbass), Georgia (South Ossetia and Abkhazia), Moldova (Transnistria), and Azerbaijan (Artsakh).

The current war is different, with Western support helping Ukraine regain much of the territory Russia seized in the first few weeks after last year’s invasion.

Still, if Slanchev is right, the two sides face an eternal war.

This could end up looking something like the Korean peninsula with a demilitarized zone between Ukrainian and Russian controlled territory, or a grueling perpetual conflict that flares up and down, eventually leading to an uneasy truce.

Either way, one thing is for sure: much more pain, for Ukraine, Russia and the rest of the world.