A novel treatment using overloaded immune cells appears to be effective against tumors in children with a rare type of cancer, researchers reported Wednesday.

Nine of 27 children in the Italian study had no signs of cancer six weeks after treatment, although two later relapsed and died.

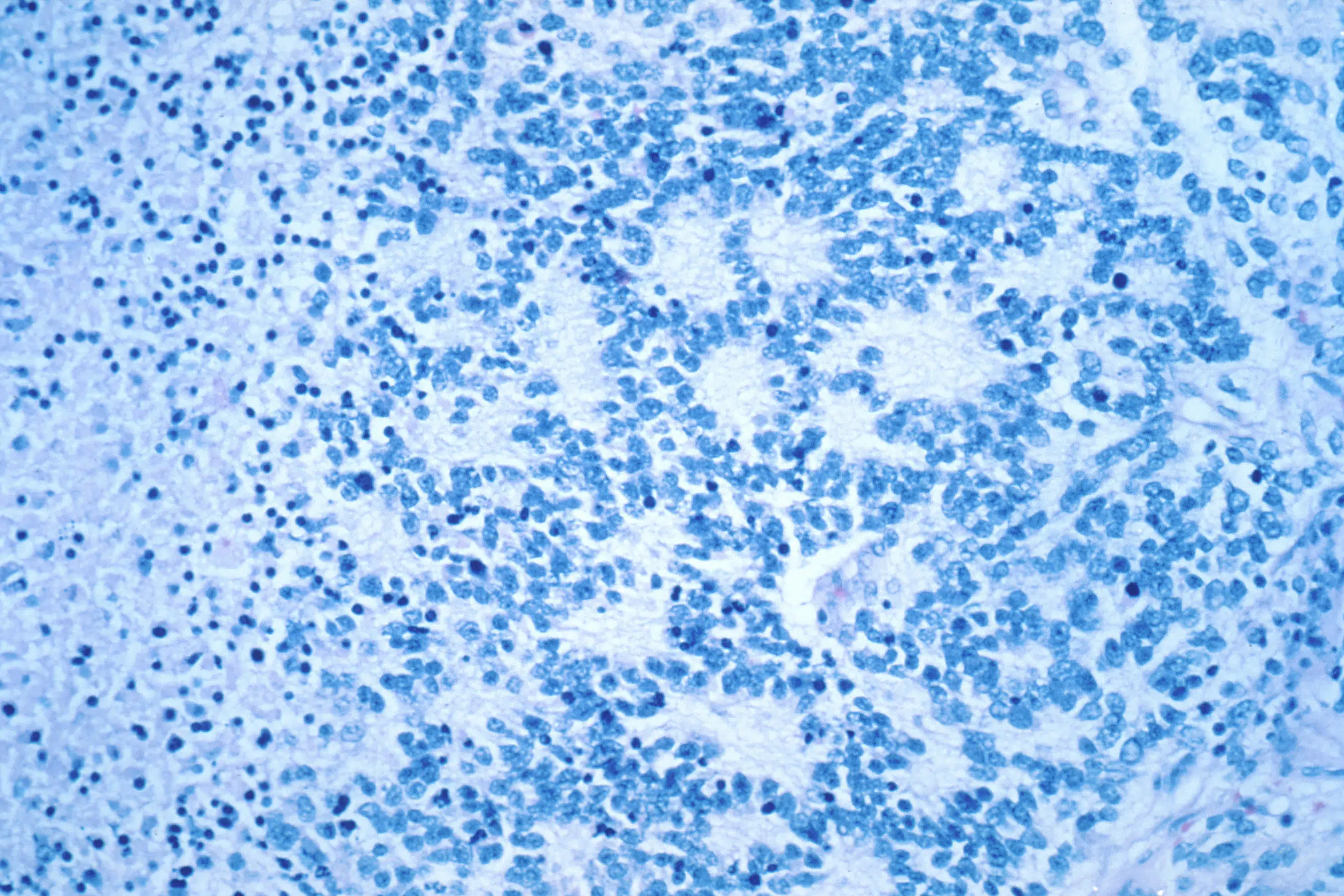

The treatment – called CAR-T cell therapy – is already being used to help the immune system fight leukemia and other cancers in the blood. This is the first time researchers have had such encouraging results in solid tumors, experts in the field said, and raises hopes it can be used against other types of cancer.

It’s too early to call it a cure for neuroblastoma, a cancer of nerve tissue that often starts in infancy in the adrenal glands near the kidneys in the abdomen.

Standard treatment can be intensive, including chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation, depending on the stage of the cancer and other factors. The children in the study had cancer that had come back or was particularly difficult to treat.

Eleven children were alive at the end of the three-year study, including some who only partially responded to treatment and received repeated doses of the modified cells.

“These children were all destined to die without this therapy,” said Dr. Carl June of the University of Pennsylvania, a CAR-T therapy pioneer who was not involved in the new research.

“Nobody’s ever had patients react like that before, so we just don’t know what it’s going to be like 10 years from now,” June said. “Certainly there will now be further trials based on these exciting results.”

CAR-T cell therapy harnesses the immune system to create “living drugs” that are able to seek out and destroy tumors. T cells from the patient’s blood are collected and amplified in the lab, then returned to the patient via an IV, where they continue to multiply.

Six CAR-T cell therapies have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for blood cancers. Some early patients were cured.

But success in solid tumors has been elusive. The latest study was conducted by researchers at the Vatican Children’s Hospital Bambino Gesu in Rome.

“They appear to have found a unique combination” to get the modified cells to first multiply and then persist to continue their cancer-killing work, said Dr. Robbie Majzner of Stanford University School of Medicine, who was not involved in the new study.

The co-author of the study, Dr. Franco Locatelli said they also added a safety switch to eliminate the cells if a patient had a severe reaction. When a patient was having trouble, they flipped the safety switch and showed that it worked, although they later determined the patient’s problem was caused by a cerebral hemorrhage that had nothing to do with the CAR-T cells.

Many of the children had a side effect that is common with CAR-T therapy — an overreaction of the immune system called “cytokine release syndrome.” It can be serious but was mild in most cases, the researchers reported.

They concluded that CAR-T therapy was “feasible and safe in the treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma.”

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.