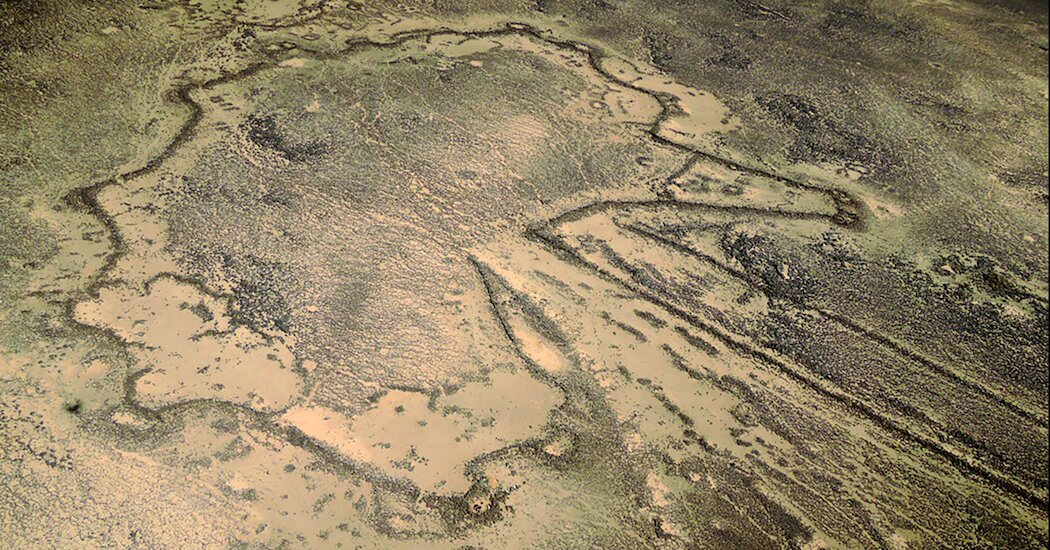

Massive prehistoric stone structures found in desert landscapes from Saudi Arabia to Kazakhstan have puzzled archaeologists for decades. Each can stretch for several miles and in overall form resembles a dragon with tail sinews.

Recent studies have established a consensus that the so-called desert dragons were used to capture and kill wild herds of animals. But how the ancient hunters conceived and perceived these grandiose structures has remained a mystery. The dragons in their entirety “are only visible from the air,” said Rémy Crassard, an archaeologist at France’s National Center for Scientific Research. “Even with our modern view of our landscape, it is still difficult for us archaeologists, scientists and scholars to create a proper map.”

dr Crassard and his colleagues were overjoyed in 2015 when they found two stone monoliths in Jordan and Saudi Arabia with precise depictions of nearby desert dragons. Engraved 7,000 to 9,000 years ago, these depictions are by far the oldest known scale architectural plans recorded in human history, the team reported Wednesday in the journal PLOS ONE. They also show how carefully the desert dragons were planned by the ancient races who relied on them.

“It’s overwhelming,” said Dr. Crassard, “to know and to show that they were able to develop this mental conception of very large spaces and put them on a smaller surface.”

In the last decade, Dr. Crassard and his colleagues used satellite imagery to identify more than 6,000 desert kites of various shapes and sizes in the Middle East and western and central Asia as part of a project called Globalkites. Other researchers have discovered stone carvings depicting these man-made puzzles during investigations and excavations.

But speaking about the previously found engravings, Dr. Crassard: “You could not assign these drawings to a specific dragon.”

When field research found the two dragon depictions in southeast Jordan and northern Saudi Arabia, archaeologists knew they were dealing with something special.

First of all, they noted the presence of three distinctive features of the dragon. There were “tail cords” that represented more or less connected rows of stones. These converge into a walled enclosure resembling the dragon’s “body”. And pits had been dug along the edges of the body. Archaeologists suggest that groups of animals such as gazelles followed or were hunted along these stone lines before being channeled into the enclosure where hunters killed the animals and used the strategically placed pits to trap any attempted escapes.

Very quickly, the team realized that these engravings matched the shape and structure of dragons seen nearby. In south-eastern Jordan, for example, dragons’ tail lines curve as they converge in enclosures – a feature also visible on the engraved stone.

“If we look at the satellite and aerial imagery we’re taking on the ground, it’s like a drawing of the actual dragons in that area,” said Mohammad Tarawneh, an archaeologist at Al Hussein Bin Talal University in Jordan and author learn of the book.

Mathematical models also showed that the dragons in the Jordan-Saudi Arabia region where the team worked were the most similar when the researchers compared the geometry of the two engravings to a total of 69 dragons from different regions. Shape comparisons with such nearby kites also revealed that the depictions were true to scale. Using geological dating tools, the researchers determined the age of the engravings and thus determined how long ago the corresponding local kite structures were.

It remains unknown whether these depictions were made as blueprints for building the kites or served as maps for hunters. The engravings could also be symbolic commemorations of the desert dragons, which may have been an important part of the cultural identity of the ancient peoples who made and used them, said Wael Abu-Azizeh, an archaeologist at the French Institute for the Middle East in Jordan and an author of the study.

Yorke Rowan, an archaeologist at the University of Chicago who was not involved in the study, said the engravings cited in the paper are a great find. He called it remarkable that the people on the ground could accurately depict things that can now only be seen in full from above. Finding this mental mastery of space opens a new window into the minds of these ancient hunters.