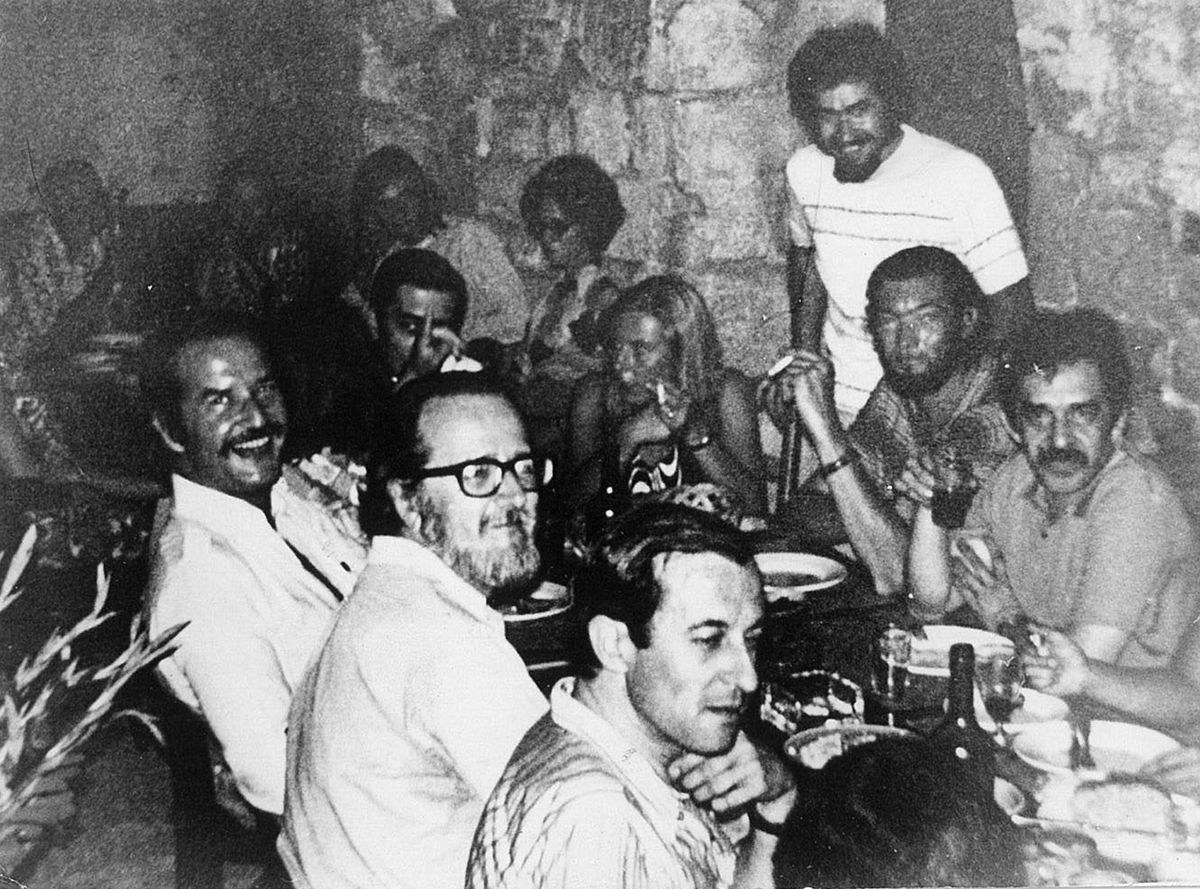

From left to right: Juan Goytisolo, José Donoso, Carlos Fuentes, Patricia Llosa, Mario Vargas Llosa, Ugné Karvelis, Abraham Nuncio, Julio Cortázar and Gabriel García Márquez, in Bonnieux, France, on August 15, 1970. Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art

From left to right: Juan Goytisolo, José Donoso, Carlos Fuentes, Patricia Llosa, Mario Vargas Llosa, Ugné Karvelis, Abraham Nuncio, Julio Cortázar and Gabriel García Márquez, in Bonnieux, France, on August 15, 1970. Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art

It’s November 1968, the Soviet Union is invading Czechoslovakia, and the Cuban regime is angered by some Latin American writers’ criticism of the island. During that year of political turbulence, Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes wrote a letter to Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa, discussing these issues, ending with the following words: “I know that you hate the genre of letters… and I’m not asking you for an answer. Yes, keep the letter for Harvard (just kidding).”

The letter was not kept by Harvard, but Fuentes knew that this correspondence would one day be of particular value, and for this reason he kept much of what he wrote and received from his writer friends: Vargas Llosa, Gabriel García Márquez and Julio Cortazar . Eventually, the letters sent between the four were kept by Princeton and Austin, Texas universities, as well as family and friends. For the first time, all these letters are gathered in a new book by Alfagura: Las Cartas del Boom, an archive of letters that can already be found in bookstores in Spain, Mexico and Colombia. It will be available in the US in mid-September.

The book contains 207 letters beginning in 1955, when Fuentes and Cortázar were just beginning to develop a professional relationship; And that lasts until 2012, when the Mexican celebrates Gabriel García Márquez’s 85th birthday. “Our lives are inextricably linked,” the author lovingly writes of a friendship that lasted more than half a century. Signature: “Your friend”.

In these letters, Cortázar is sometimes referred to as “High Cronopio”, Fuentes as “Aztec Eagle”, Gabo as “Colonel” and Vargas Llosa as “Great Inca Chief”. None of the four had yet achieved international fame, but they would soon be releasing their pinnacle works: The Death of Artemio Cruz, Hopper, Heaven and Hell, The City and the Dogs and One Hundred Years of Solitude. Their manuscripts were read among themselves, recommendations made, encouragements given, but their blind spots were also criticized. The Book of Letters is a reminder that no writer made literary history by writing his novel alone: he needed a community willing to read them, write rave reviews, and commend them for an award. In short, the new book is a reminder that a writer is also his friend.

“Las armas Secretas is the finest collection of short stories ever written and published in Latin America,” an emotional Fuentes wrote to Cortázar in 1962 about the Argentine’s new book. The Mexican writer in particular is a great companion to the other three: he recommends translators and publishers in Latin America and the US, asks them about the publication dates of their next novels in order to write positive reviews in magazines, and has a holistic vision of what they do together .

“Doesn’t it seem to you that every good Latin American novel liberates you a little, allowing you to narrow your own terrain with enthusiasm, to immerse yourself in what is yours with the fraternal awareness that others are perfecting your vision as it is ? were, with that?” asks Fuentes Cortázar, as if the four were making a single great literary work.

Newsletter

Analysis of current events and the best stories from Colombia, every week in your mailbox

GET THIS

“Carlos Fuentes is the great promoter of the boom, we owe the existence of this book to him,” says Mexican writer Javier Munguía, co-editor of this new volume of letters. Gabo and Cortázar weren’t very good at keeping letters, he explains, and Vargas Llosa kept some he received but no copies of the letters he sent. Fuentes has kept it all, like a visionary who trusts in his greatness and that of his friends. “He was more aware than the others that this file could be important in the future,” adds Munguía.

The book about the four friends is the editorial work of four other fans of boom literature: Carlos Aguirre, biographer of the novel La Ciudad y Los Perros; Gerald Martin, biographer of Gabriel García Márquez; the Peruvian academic Augusto Wong Campos and Munguía. The latter, from Mexico City, explains to EL PAÍS that this book of letters was an initiative born in 2019 in a convivial circle where the four friends and their obsessions are. “The result is that this isn’t a side work about the authors, but rather reveals a lot about their opinions and the political tensions between them,” says Munguía.

In Las Cartas del Boom there are also invitations to eat hallucinogenic mushrooms in Mexico and even unexpected financial advice. “Another thing is the spending in the socialist countries. With the blackmail that they are very poor and we are their friends, they milk us out,” an outraged García Márquez wrote to Vargas Llosa in 1968. He wonders if they would continue to publish their works in left-ruled countries. “It’s practically a philosophical contradiction that the exploiting countries exploit us less and respect us more than those who claim not to be exploiters.”

“A writer’s correspondence is a fundamental document for understanding the creative process of his works,” says scholar Álvaro Santana-Acuña, biographer of the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude and well acquainted with García Márquez’s archive, to EL PAÍS. “In this case, we are facing the first publication of the letters exchanged by the most important writers of the Latin American boom, and this had never happened before,” he adds.

A few letters had already appeared in book catalogues, in individual exhibitions, but never in the form of a conversation. The special thing about it, explains Santana-Acuña, is that one can transparently see how the four “believe in the possibility that Latin America will, for the first time, begin to publish first-class literary works and achieve international success.”

Time flies and friendships don’t always survive. “Your behavior has put your friends in Havana in a more than awkward position,” Cortázar complained to Vargas Llosa in 1969 after the Peruvian writer refused to visit the island for a cultural event. Fidel Castro’s regime was already beginning to demonstrate its authoritarianism towards writers, a political issue that would lead to irreconcilable fighting between the four friends. Back in 1971, Cortazar saw divorce between friends as something inevitable: “There’s something worse, and it’s feeling like things that I love very much can break, long-standing friendships and very deep affections.”

The story is already well known: Cortazar and García Márquez divorced Vargas Llosa, and after the Argentine’s death in 1984, the Colombian and the Mexican maintained the most enduring friendship. The new Latin American novelists are now writing in Gmail or WhatsApp, where the memory is shorter and now depends on the number of gigabytes. The history of literature may now be writing its way into a spam folder. But the friendship that changed the history of Latin American letters in the 20th century still lives on in the two hundred letters four authors sent each other and four co-editors saved.

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS newsletter on Colombia and receive all the latest information about the country.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits