These days I am reading Las cartas del Boom, a volume of more than five hundred pages filled with uninterrupted joy, at least for those who, like me, suffer from the incurable vice of correspondence. I don’t know how long this fever has gotten the better of me, and I’ve proved by scandal that not everyone shares it, but the private letters of writers have always occupied a significant part of my life as a reader. In one of the most difficult moments I have ever experienced, a collection of letters has helped me a lot: those written by Ernest Hemingway and his editor Maxwell Perkins over the course of a little over twenty years. There was a whole guide there on the one thing great novels can’t teach a novelist: how to deal with frustration and discouragement, or in other words, those strange forces that come from without – envy, resentment, slander and gossip – and also with those that come from within – cynicism, insecurity, bitterness and the sense of failure -. I still have the book within reach, like a good friend’s phone. And there are very few of them.

But I get lost. Letters from the Boom is a comprehensive compilation of the correspondence between the four most important novelists of this generation, who shared the strange fact of being great writers and great friends at the same time. In order of appearance: Julio Cortázar, Gabriel García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes and Mario Vargas Llosa formed or occupied a sort of central place in Latin American literature (the Cogollito, as José Donoso called it), to the monumental fury of so many then as now. es, another great novelist who felt both inside and outside the group, and who has left his testimony of this in a book that is both delightfully garrulous and irrepressibly serious: Personal History of the Boom). I have for me that they continue to shape it, because the time that puts everything in its place has passed perhaps less leniently for some novels than for others – I can no longer read Manuel’s book, for example – but the work as one The collective of these novelists remains—and I fear increasingly will be—one of the most solid and truthful phenomena in 20th-century literature.

It must always be repeated, a little wearily, that this movement called Boom was by no means limited to these four names, but in the same breath one has to admit the inescapable truth that one cannot speak of Boom without beginning with them. Perhaps we have become accustomed to his presence and the mention of his books because our relationship with all of them is already celebrating their years, and perhaps for us they have turned into a landscape and sense of wonder that readers of other decades, but the coming together of their masterpieces in just a few years must be a source of fascination, or at least of bewilderment, to anyone who knows the almost insurmountable difficulty of writing a decent book. The four editors of this book—in alphabetical order, not by publication: Carlos Aguirre, Gerald Martin, Javier Munguía, and Augusto Wong Campos—seem to be well aware of this. In an informed and insightful prologue, also written gracefully, they identify the four characteristics of this sacred game that defined the relationship between these novelists: writing total fiction, friendship, political vocation and the international impact of their books. I think they’re spot on when they cite as a premise a line Vargas Llosa wrote in a letter to Carmen Balcells: The ideal novel should be both The Three Musketeers and Ulysses; in other words, a novel that deals with adventures without ceasing to be absolutely modern.

The focus of the conversation – not just political, but also literary – is Cuba. The boom is inconceivable without the Cuban Revolution, which appears very soon after the first letter in the life of these novelists; And not just because it brought them together and brought a common goal to the table, but because it bothered them so much that it was also one of the reasons for their disagreements. But more than that (and this is also pointed out in the forewords), the great novels of this generation tried to do in fiction what the Cuban Revolution tried to do in reality: to rewrite history. Latin American history, so rich in lies and interesting distortions, encountered the troublesome truths of fiction in novels like One Hundred Years of Solitude, The Death of Artemio Cruz, or Conversation in the Cathedral; On the other hand, the revolution that tried to impose absolute categories on troublesome human relativity would end up illustrating the mistake that can be made in transferring the ambitions of literature to political life.

But none of that would be enough to explain the happiness of reading this book, or it wouldn’t be if we didn’t consider the most important reason: these four authors were also exceptional correspondents. I already knew of Cortázar, whose five volumes of letters have the only flaw of not being ten or twenty, because he was so intelligent and his humor so cultivated and so free from presumption that each page makes us want to go on. I hear that voice to the end of days. But in Las cartas del Boom there is also the intelligence and erudition of Carlos Fuentes, who seems to have read and found time to write all the books of yesteryear and all his friends now; and the quick wit of García Márquez, who wrote his letters with the stroke of a pen in the same prose that knows no platitudes that he used for literature. Vargas Llosa is perhaps the least enthusiastic about his letters, and more than once he describes himself as a lousy correspondent, for good enough reason that he didn’t relish the task of being one. But in the letters he also portrays himself: generous, tirelessly curious and committed to the art of fiction to the death.

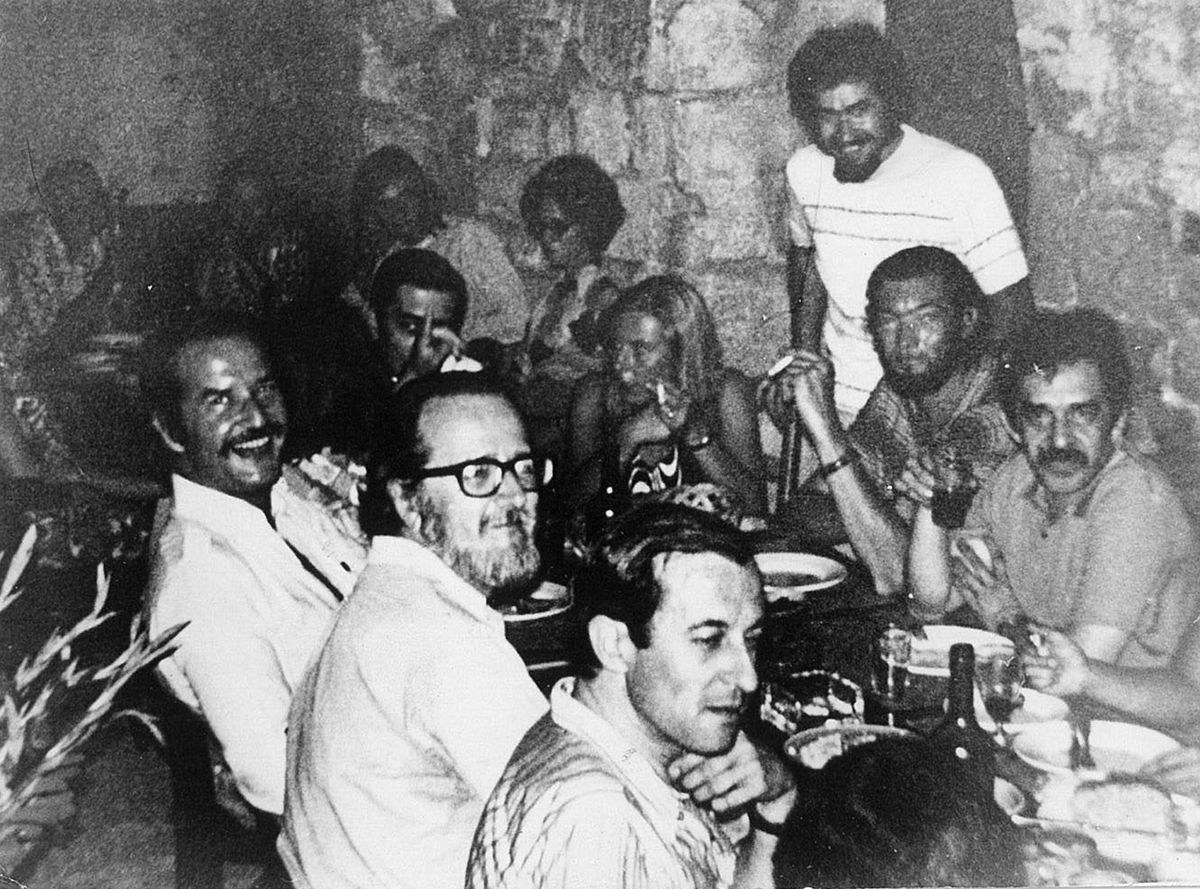

The book is full of great moments: the writing process of One Hundred Years of Solitude, Cortázar’s critical readings of Fuentes and vice versa, the constant attacks they all receive from what Fuentes calls “the pygmies”, the deep irritation that makes their success, the upheaval of the Padilla case, the rejoicing of some at the good things that are happening to others. And the strangest thing about our ubiquitous image culture, for our overly photographed world, is that there is only one image of the four novelists together. It was recorded at a restaurant on August 15, 1970; they all come from a play by Fuentes: The one-eyed man is king; They went to Julio Cortázar’s house in Saignon, in the south of France. They would continue to correspond but would never be together again. The closest they came to being cast together was in the final chapter of Terra Nostra, the massive novel Fuentes published in 1975 in which their characters meet. That has to be enough for us.

Newsletter

Analysis of current affairs and the best stories from Colombia, every week in your mailbox

GET THIS

Juan Gabriel Vasquez He’s a writer

Subscribe here to the EL PAÍS newsletter on Colombia and receive all the latest information about the country.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits