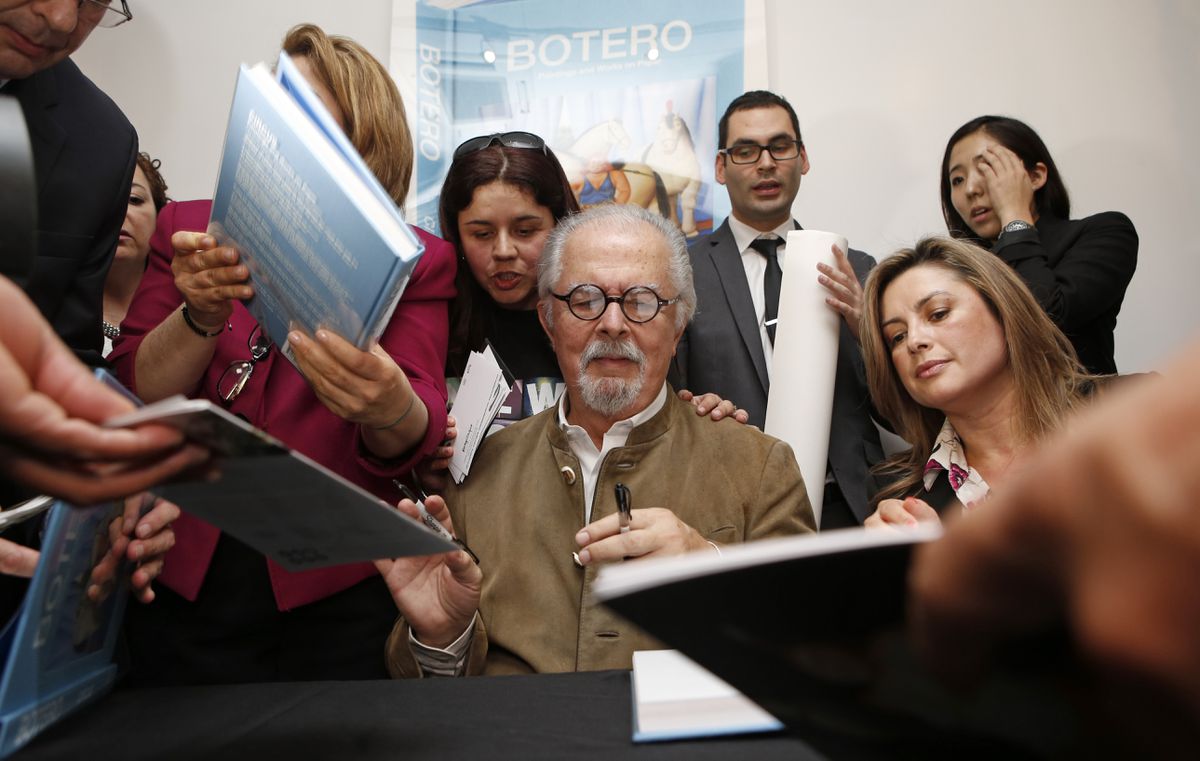

The painter and sculptor Fernando Botero, who died on September 15, was the last survivor of the generation of modern artists that emerged in Bogotá in the 1950s under the protective mantle of the art critic Marta Traba (1930–1983). This hard core of the generation also included the artists Alejandro Obregón, Édgar Negret and Eduardo Ramírez Villamizar, and painters such as Enrique Grau and Guillermo Wiedemann, all deceased, also took part. Likewise, Botero was most likely the last great figure of the modern project in Colombia and an intellectual elite that included writers like Gabriel García Márquez or Álvaro Mutis and architects like Rogelio Salmona or Fernando Martínez Sanabria. Due to his great public recognition and media presence, Botero represents an important reference in the processes of internationalization of Colombian culture in the context of the Cold War (1947-1991) and the so-called Latin American boom (1960-1970).

Of the above group of painters (nicknamed “Los Untouchables” by the critic Fausto Panesso in 1975), Botero from Medellín was the one who achieved the greatest international visibility. After winning first prize at the National Salon of Artists in 1958 with his painting “Camera degli sposi” (Homage to Mantegna) and his early participation in exhibitions at the Pan American Union in Washington (1957) and the Guggenheim Museum in New York (1958 ) and at the São Paulo Biennale (1959), Botero looked back on a career spanning more than 70 years, during which he continuously and frantically produced paintings, drawings and sculptures.

A few years after his move to New York (which took place in 1960), Botero’s work took a turn: his “classical period” or “training period” (1949-1965), praised by Latin American critics of the time, is a work characterized by the thick and visible brushstrokes, unnatural colors, contrasts between opposites, hieratic and monumental figures, political criticism, large formats and the absence of narrative, he gave way to what is now popularly known as his “style”. . in which the volumetric increase predominates (which Botero had discovered in the 1950s in Quattrocento painting and in pre-Hispanic Mexican art), clean and defined oil paint, invisible brushstrokes, natural colors (blue for the sky and green for the grass), and a certain baroque narrative that recalls the paintings related to the lives of the saints.

Botero iconography in this final era is based on the repetition of archetypes deeply rooted in Latin American folklore, resulting in an easy identification between the local viewer and the artist. This second period (1966-2023), the most commercially successful, has not always had great critical and academic luck, it has been seen as a period of formula and repetition and a distinctive mark on the international market: a work that enters cultural history rather through a checkbook than through collective meaning.

Undoubtedly, Botero’s visibility between the sixties and nineties was influenced by several factors that would be worth analyzing in the light of the present: the search for fame, excessive presence on networks, excessive media coverage and an inflationary art market. First, Botero quickly recognized the importance of publishing his own work (he is by far the Colombian – and perhaps Latin American – artist with the largest number of monographs and catalogs, frequently published by his gallerists and collaborators). In this sense too, the press was one of its most powerful allies, sometimes relying on the dithyramb (which Marta Traba recognized as early as 1961 in the article No tanta gloria in the magazine Estampa de Bogotá) and on national feeling to make collective validation or recognition difficult. Before Instagram and TikTok, Botero understood human networks and the power of the image and the analogue press and made his war chariot out of it.

Second. Unlike other artists of his generation, for whom too close proximity to the market could “pervert”, interfere or distort the most authentic creation, Botero had no qualms about marketing his works through numerous galleries and auction houses in the United States and Europe, and He cared little (at least since the 1960s) about the opinions of critics, curators and museum directors. In the case of Botero, it is likely that this increased commercialization, subject to the tastes of collectors, ultimately changed the artist’s practice. These days, this is the way many artists operate via Instagram, with the number of followers or likes of a painting (usually works that demonstrate technical skill rather than theory or process) being more important than critical opinions or field opinions. . This can distort the motivation for creating a work, which, through a system of rewards (measured in likes), can be subject to external taste rather than the artist’s intellectual searches or his aesthetic, poetic or political beliefs.

Newsletter

Current events analysis and the best stories from Colombia, delivered to your inbox every week

GET THIS

Third. Botero recognized the importance of philanthropy to promote his artistic work: since the 1970s he donated (his own work and that of others) to the Museum of Antioquia (Medellín), the Museum of Contemporary Art (Caracas) and the National Museum (Bogotá). or to the Bank of the Republic (Bogotá), this without his numerous donations and sales of large-scale sculptures to public spaces in Bogotá, Medellín, Bucaramanga, Cartagena, Caracas, Madrid, New York, Buenos Aires or Paris, to name just a few cities. Its extraordinary visibility in public spaces and memory institutions, especially since 2000, is a rarity in the Colombian art space, characterized by the economic insecurity of artists (a powerful and creative guild) and institutions.

Finally, unlike the abstract expressionism of the fifties or the conceptualism of the seventies, Botero’s art tells easy-to-understand stories, in a figurative key, with a large dose of humor and while maintaining a style recognizable to the market: let’s remember: “ “Style “ is one of the commonplaces of the modern art market, as it makes the work easily recognizable and gives the collector a recognizable reason for social demands. This “simplicity” or speed in delivering the message is now a prerequisite for mass consumption of information and one of the elements of clickbait journalism or the Twitter model. However, art is not always about how easy it is to transmit a predetermined message, but rather, precisely in the discussions it generates, it can be a message in permanent construction, a new world to be discovered applies, with edges that go beyond the immediacy or speed that it generates is often required of the headlines and networks of our time. Art can continue to be this free refuge, this little field of discussion where the world is cooked. And the first Botero, the one from the early days, the one from his youth, comes only to teach us the power of art without ties, the fire of authentic creation and the path of permanent search.

Halim Badawi He is an art critic and director of the Arkhé Archives in Madrid.

Subscribe to the EL PAÍS newsletter about Colombia here and receive all the important information about current events in the country.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits