This text is part of the special section Professions and Careers

Environmental groups have been fighting to protect nature for more than half a century. Behind this eternal standoff between activists and industry, scientists are working to measure the concrete consequences of pollution. A look at a constantly evolving field, ecotoxicology.

In 1962, biologist Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, a book about the devastating effects of pesticides. This work is considered by many to be a founding element of the environmental movement in the West. For the first time, the harmful effects of anthropogenic activities on the environment became visible in broad daylight.

Since then, a lot of water has flowed under the bridges; Other environmental scandals made headlines and stricter measures were also introduced to better control human activities that could harm the environment. At the same time, the profession of ecotoxicologist emerged.

Ecotoxicology is an interdisciplinary science that studies the effects of chemical pollutants on ecosystems and the organisms that live there. In simple terms, the mission is to monitor the environment, develop risk management strategies and communicate the results. Ecotoxicologists can work for companies, government agencies and research institutes, as well as NGOs.

“It is difficult to quantify the number of ecotoxicologists because there is no professional association or undergraduate degree in the field, but I can say categorically that the profession is growing,” says Claude Fortin, co-director of the Quebec Ecotoxicology Research Center. The term didn’t even exist in 1970… Today it is a sought-after expertise. »

From Burkina Faso to Montreal

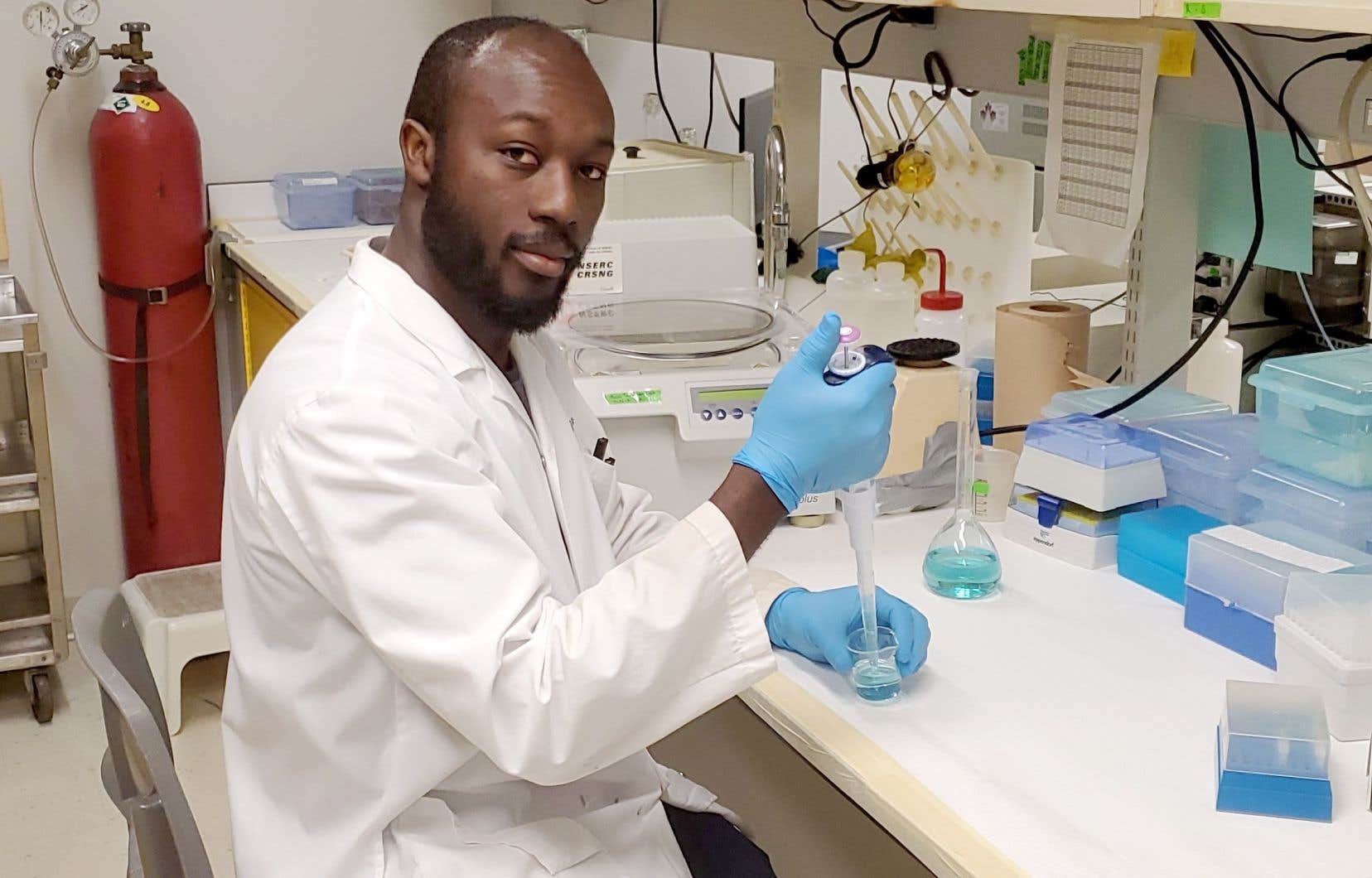

Yannick Arnold Nombré never thought he would one day study freshwater mussels from Quebec. The 32-year-old researcher is originally from the Bobo-Dioulasso region of Burkina Faso and is a doctoral student in ecotoxicology at the University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM). When he moved to Quebec in 2016 to continue his studies, the culture shock was great, but not necessarily for the reasons you might think.

“My integration went quite well, especially thanks to the presence of the family I had here; “They helped me a lot,” explains the man, who earned a master’s degree in environmental sciences at UQAM. The most difficult thing was adapting to the academic system, but also becoming aware of the scale of the ecological crisis on a personal level. »

Yannick Arnold Nombré has always felt connected to nature. He nostalgically talks about childhood memories, such as the time when he gardened with his uncle. In school, environmental education was limited, with the exception of desertification, a particularly devastating phenomenon in Burkina Faso.

“When I arrived in Quebec, my vision changed a lot as I learned all about the environmental problems,” he admits. It was very shocking and disgusting, it almost made me depressed. »

Fortunately for the Burkinabè, morale has improved over time, thanks in part to his job. The doctoral student is convinced that he can be part of the solution, a mentality that, in his own words, helps him a lot.

“Five years ago, I wrote on my resume that my professional goal was to help protect and restore the environment,” he says. Every year when I update my resume I see this goal and it gives me confidence that I am on the right path professionally and personally. »

Protect the mussels better

After completing his master’s degree, Yannick Arnold Nombré took his first steps on the job market by completing an internship at the Ministry of Environment, Fight against Climate Change, Wildlife and Parks (MELCCFP).

“The focus of the internship was on aquaculture wastewater discharge regulations (wastewater flowing from aquaculture facilities), he explains. It trained me on aquaculture issues around Quebec; I learned a lot. »

One thing led to another and the scientist began a doctoral thesis in ecotoxicology with the main topic of freshwater mussel health. A problem that is as niche as it is fascinating, he thinks.

“I study the effects of pesticides on freshwater mussels,” he explains. The data collected will be used to develop a diagnostic tool for the health of these mussels in the agricultural rivers of Montérégie. The primary goal is to better protect these species in the future. »

For Yannick Arnold Nombré, his time in the laboratory and in the field provides a hopeful look into the future. When we ask him about his environmental optimism, we are still cautious on the other end of the phone.

“If you could see my face now [rires]. “I ask myself a lot of questions, especially whether I want to have children or not,” he admits. I don’t know if I’m optimistic, but I’m still hopeful. Hope is important in our world. »

Between optimism and realism, one thing is certain: this year will be special for the ecotoxicologist. The reason ? He will visit Burkina Faso for the first time in seven years. Lots of quality family time awaits you at home, a temporary but extremely effective solution to existential questions.

Women are still underrepresented in the environment

This content was created by Le Devoir’s Special Publications team, reporting to Marketing. The editors of Le Devoir did not take part.