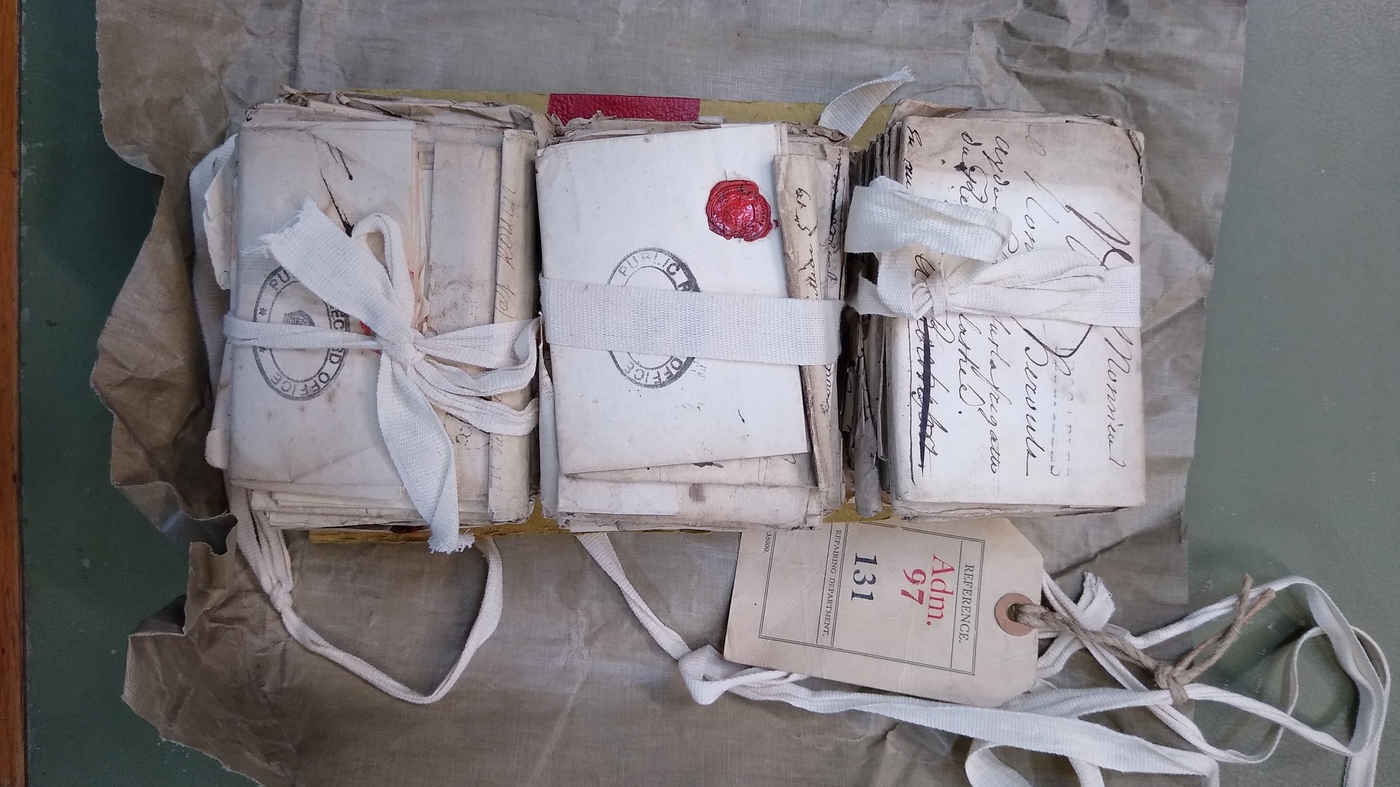

The letters before they were opened.

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Hide caption

Toggle label

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

The letters before they were opened.

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Numerous French love letters from the mid-18th century have been opened and examined for the first time since they were written.

The letters – sent to French sailors by wives, siblings and parents – never reached their intended recipients, but offer a rare glimpse into the lives of families affected by the war.

“I could spend the night writing to you,” Marie Dubosc wrote to her husband. “I am your forever faithful wife. Good night, my dear friend. It’s midnight. I think it’s time for me to rest.”

Dubosc would not have known that her husband had been captured by the British and that he would never receive her message. She died a year after sending the letter and probably never saw him again.

The letters sent between 1757 and 1758 during the Seven Years’ War were mostly addressed to the crew of the warship Galatée and were forwarded from port to port by the French postal administration in the hope of reaching the sailors. But when the British navy captured the Galatée in April 1758, French authorities forwarded the batch of letters to England.

There they remained unopened for centuries until historian Renaud Morieux of the University of Cambridge discovered them in the digital inventory of the British National Archives. He checked the box in the archives, not knowing what he would find inside.

Inside the box were three packets of letters wrapped in white ribbon.

“Basically I had to pull the string, a bit like a Christmas present,” he told NPR.

“My heart started beating faster and I thought, ‘Ooh, this looks like really cool stuff… There might be some secrets in there.'”

Anne Le Cerf’s love letter to her husband Jean Topsent, in which she says: “I can’t wait to own you.” and signs “Your obedient wife Nanette.”

he National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Hide caption

Toggle label

he National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Anne Le Cerf’s love letter to her husband Jean Topsent, in which she says: “I can’t wait to own you.” and signs “Your obedient wife Nanette.”

he National Archives/Renaud Morieux

The 104 letters are written on heavy, expensive paper and some have red wax seals. But they contain the words of common people rather than those of aristocrats, says Morieux – voices often missing from the historical record, such as those of the wives of sailors and fishermen.

“These letters tell us how people from the lower classes dealt with the challenges of war and the absence of their relatives and loved ones,” says Morieux, “and how they managed to overcome distance and fear of uncertainty.”

Morieux spent months deciphering the letters and published his findings on Monday in the French historical journal Annales. History, social sciences.

In a letter, Marguerite Lemoyne, a 61-year-old mother, scolds her son Nicolas Quesnel for not writing:

“On the first day of the year [i.e. January 1st] You wrote to your fiancée… I think of you more than you think of me… In any case, I wish you a happy new year full of blessings from the Lord. I think I’m for the grave, I’ve been sick for three weeks. Compliments to Varin [a shipmate]it’s just his wife telling me her news.

Marguerite’s letter to her son Nicolas Quesnel (dated January 27, 1758), in which she says: “I am for the grave.”

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Hide caption

Toggle label

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Marguerite’s letter to her son Nicolas Quesnel (dated January 27, 1758), in which she says: “I am for the grave.”

The National Archives/Renaud Morieux

Morieux told NPR that Lemoyne’s complaint shows “universal” family dynamics.

“The son, who is at sea, only writes to his fiancée, and the mother is really upset about it,” Morieux said. “And here you get the feeling that there’s some kind of… really long, age-old phrase about tensions in the family between the mother and the daughter-in-law.”

Morieux said the letters also show the difficulty of long-distance communication in the 1750s. Many of the senders, like Lemoyne, were probably illiterate and dictated their messages to a scribe.

Additionally, sending a letter to a ship that was constantly underway during wartime was difficult and unreliable, and families often sent multiple copies of the letters to different ports.

To maximize the chances of successful communication with a loved one, each letter contained multiple messages, often from different families and addressed to multiple crew members.

“And so not only are they covered in ink from top to bottom…The sentences are written left to right, but also in the margins,” Morieux said.

For Morieux, the letters show how communities remain resilient in times of crisis.

“It’s about the power of the collective. The point is that these people can only survive if they rely on others.”

Christopher Intagliata and Gabriel Sanchez contributed to this report.