This is the first time this viral behavior has been observed.

This is the first time this viral behavior has been observed. ![]() Rory Morrow Meteored United Kingdom November 18, 2023 1:00 p.m. 4 min

Rory Morrow Meteored United Kingdom November 18, 2023 1:00 p.m. 4 min

For the first time, scientists have observed unusual behavior in some viruses, where one virus binds to anotherlike a vampire to reproduce.

These viral relationships, in which one virus (the satellite) depends on a second virus (the helper) to complete its life cycle, have been known for some time. But until now, No one had ever seen a satellite virus physically attach itself to its unwitting partner.

This behavior was observed in a type of bacteriophage – a virus that infects bacteria – that systematically binds to another bacteriophage at its “neck,” where the main body of the virus attaches to the tail. The researchers describe their findings in a new study published in the Journal of Microbial Ecology.

“When I saw it, I said to myself: I can’t believe itsaid Tagide deCarvalho, lead author of the study and researcher at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC). “Nobody has ever seen a bacteriophage – or any other virus – attach to another virus.”

Satellite bites

It was these “vampire viruses,” as they were of course also called discovered entirely by chance in a student’s bacteriophage sample sent to the sequencing laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh.

The sample contained not only a large genetic sequence of the expected bacteriophage, but also something smaller that didn’t match anything the researchers knew. It wasn’t until the team brought deCarvalho and a transmission electron microscope that they realized what was happening.

Most satellite viruses have a special gene that allows them to integrate into the DNA of the host cells they invade, such as bacterial cells. They still need a helper virusbut they just need it in a different location in the same cell, the study authors explain.

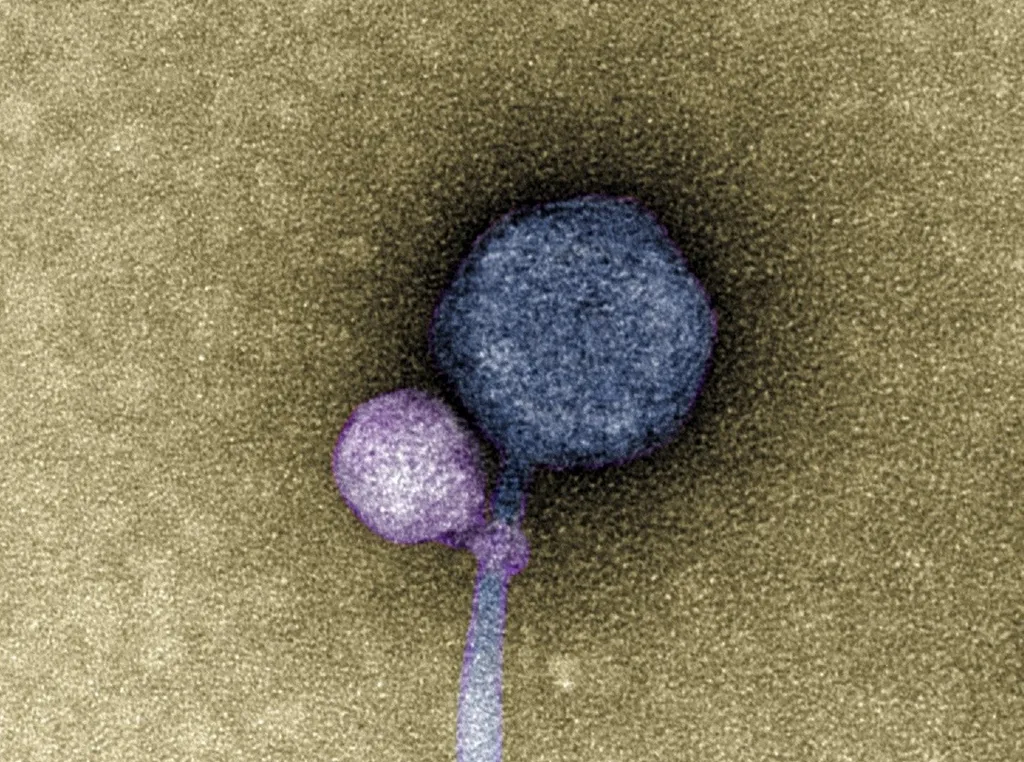

Satellite bacteriophage (left) attached to the larger helper bacteriophage (right). Photo credit: Tagide deCarvalho/UMBC.

Satellite bacteriophage (left) attached to the larger helper bacteriophage (right). Photo credit: Tagide deCarvalho/UMBC.

But the satellite virus discovered during their research does not have this gene. Since it cannot integrate into the DNA of the host cell, it has to stay close to its assistant when it enters the cell to survive.

“The binding now made perfect sense,” said Ivan Erill, co-author and professor of biological sciences at UMBC, “because how else are you going to guarantee that you get into the cell at the same time?”

A timeless relationship

Researchers found that 80% of assistants wore satellites around their necksand those that did not often showed evidence of previous bonds in the form of remaining tendrils that Erill resembled as bite marks.

Furthermore, they figured this out These two viruses have evolved together over a long period of almost 100 million years. This suggests that many more such cases may remain to be discovered. The team hopes to explore this in future research, while also studying how exactly the satellite virus binds to its helper.