FIRST PARK which could not accommodate Jocelyn Alo is 100 yards from the ocean and 100 yards from the house where she grew up. A fence now separates the backyards from the football field, and makeshift signs dot the road that skirts the beach along Oahu’s northeast shore. Keep the country in one reading, and the New City, which is a pity, in another. Everyone wants a piece of heaven, or at least a piece of what others think heaven is worth. Local Hawaiians know this story; it has long settled in their bones.

Five generations of the Alo family have lived in this wonderful place, in the shadow of razor-sharp green mountains, the peaks of which are shrouded in clouds. Jocelyn grew up like her father, Levi, and his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather before him: on a 2-acre lot with six family homes on Kukuna Road in Howula. At the end of Kukuna – Hawaiian for cultivation, which is fitting – there are two iconic coconut trees that serve as a sort of gateway to the beach. Beneath them, Levy proposed to Jocelyn’s mother, Andrea, and a few years later, the family scattered the ashes of Levy’s father, Pete, at the foot of those very trees.

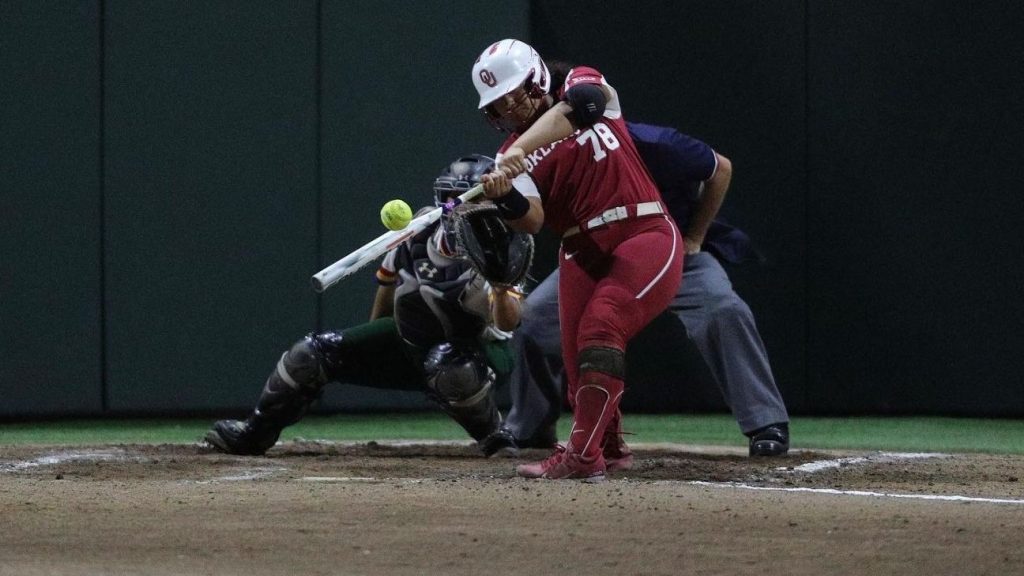

Over the years, more houses have appeared on the plots surrounding the Alo complex, but the charm remains. Chickens run from yard to yard, heedless of property lines, and the breathtaking mountains, now famous for being the setting for the Jurassic Park movies, are so bright that you look at the world through a green filter. Some changes are inevitable; Levy and Andrea moved closer to Honolulu to make it easier to get to the airport on their trips to the mainland to watch Jocelyn, the Oklahoma Sooners slugging team who broke the NCAA softball record for home runs on Friday night when she hit his 96th career homer. at the University of Hawaii vs. the University of Hawaii.

2 related

But when Jocelyn – full name Jocelyn Aloha Pumehana Alo – was 4 years old, there was no fence separating Alo’s houses from the stadium. She and Levi would go 100 yards with a bat, a bucket of balls, and an unwavering belief—and yes, more than a little fear—that this little girl has the talent to take her far away from Alos’s life. plunged into this land. The thousand shots a day that Levy threw at her, 500 in two separate sessions, a figure that sounds apocryphal but everyone swears it’s true.

Her talent took them further and further away from this village and from the people who gave it essence: to a team of travelers in Southern California, where Levy and Jocelyn rented a tiny apartment next to a football cage in Orange County and work to create talents that all more and more parks could not accommodate. From summer tournament to summer tournament, from Florida to Georgia to New York, each of them has a chance for better competition, more exposure, more opportunities. Talent was like a gravitational pull; people in neighboring fields left their daughters’ games to watch her hit. The father knew that his daughter had the ability and determination to do great things, and he was willing to make the sacrifice—and impose the same sacrifice on his daughter—to give her the best chance of achieving it.

His beliefs were first confirmed on the mainland at a BYU camp when Jocelyn was in seventh grade. She kicked the ball so fiercely that she was considered a threat to girls her age, so they transferred her to play with high school girls, and she also put fear in their eyes. At the end of camp, the BYU coach presented Jocelyn with her Division I offer, but took Levi aside and said, “If she keeps hitting like that, she won’t go to BYU.”

When they were at home, Jocelyn practiced running through the hills at the mountainous tip of Kukuna. “If that’s enough for Walter Payton and Jerry Rice,” says Levy, “it’s good enough for us, too.”

The stories pile up one after the other. Here’s one: Jocelyn High’s baseball coach, Todd Koishigawa, struggled to motivate his starting catcher. Koishigawa saw potential in the child, but everything he tried to do seemed to fail. So one day he decided to bet big: he brought Jocelyn to the baseball field from softball practice and announced to his team that from that day on, Alo – at that time a catcher – would play with the baseball team.

Koishigawa watched the reaction of his catcher and immediately realized his mistake. “His face drooped,” Koishigawa says. “He knew that if she played baseball, he would have no chance of beating her.”

Koishigawa, who later became a scout and coach for the Diamondbacks system, ran the game on Oahu. Jocelyn and Levy were there almost every day when Jocelyn was in high school, and Koishigawa says, “We used to drive the car to 90 mph just to watch her missile line crash into the back of the cage.”

Oklahoma Hall of Famer Patty Gasso stood on the field Friday night and turned to wave to the Alo family—many, many—gathered in front of the University of Hawaii third base dugout. me to greet Jocelyn after her record breaking performance. “Look at the history of Jocelyn Alo and the history of this family. Her father spent so much money to bring her to the mainland – a huge amount of money to bring her to a competitive level. a completely different level that we don’t even know about on the mainland.”

THE END WAS annoyingly slow. She beat the No. 95 homer to equal the record set by former Sooner Lauren Chamberlain against Texas State on February 20. This Homer was like a siren call to college softball teams across the country: don’t give up. record holder.

Alo walked, repeatedly, incessantly, without need. She was beaten sixteen times in the next eight games, and this strategy rarely seemed to have a purpose; in seven of those eight games, the undefeated ranked No. 1 Suners defeated their opponents.

Two weeks ago, Chamberlain sat in the stands at the Mary Nutter Collegiate Classic in Palm Springs, Calif. and was confident she would see Alo beat her record over the five games the Sooners played. “I just care about her as a person so much that I can’t help rooting for her,” Chamberlain said. “This record is not broken every year. I had it for seven years, and I enjoyed every minute. I’ve benefited a lot from it and now Jocelyn deserves it.” Fans filled the field to see Alo break the record. Volunteers wandered around the field fence, determined to return the record-breaking ball. Instead, the tournament was the beginning of a slow, frustrating process.

The disappointment came to a head in the third inning of the Sooners’ 8-0 win over Cal on Friday afternoon. Alo deliberately walked around when no one was on base and the Sooners went up eight runs, and the crowd, which included the softball team from Campbell High School, Alo’s alma mater, reacted with anger and disbelief. As the inning ended, Gasso stepped out of the Sooners’ dugout and had a friendly but pointed chat with Cal’s coach Chelsea Spencer.

“I have to tell you the truth,” Gasso said, trying not to single out Spencer. “I respect these coaches who served her. It’s a competitive sport, and if you want to see what your pitchers are made of, put them in front of one of the best hitters and see what happens. I respect every coach that has allowed their pitchers to harass Josie, and many times they have been very successful. But if you’re afraid of being blown up on social media, what does that mean for this sport? Let’s “.

But in a twist that somehow made it all logical, Alo landed a two-punch hit in the dead of night on Friday against Hawaiian pitcher Ashley Murphy, Sr., who challenged Alo with a spin ball up and down over the plate and watched him boomerang out. out of bounds in the right center of the field, about 40 feet above the wall.

(“I sincerely respect [Hawai’i coach] Bob Coolen,” Gasso said. He could have had every reason to say, “Not in this Hawaiian field.”)

Alo practically hovered around the bases, running from one to the other with her index finger raised triumphantly. After placing third, she threw a traditional Hawaiian hand gesture into the air and waved her fist at her family in the stands. Her teammates crowded around the plate, and later she emerged from the dugout to the curtain call with a lei around her neck. Her reaction was equal parts exuberance and relief.

“A huge relief,” she said. “Now I feel that everyone can relax and we can improve our game even more. And you know what’s funny? I think people will start referring to me normally again. They just didn’t want to use it.”

It was behind her: Levi, Andrea, Nita’s grandmother, and any number of Alos and extended Alos waiting to celebrate in front of third base’s dugout. “It’s not really a relief,” Levy said, “because I knew she was going to do it.” Andrea, however, said: “This is a huge relief. Now she doesn’t have to think about it.”

The homer was Alo’s eighth of the season, and the eight-game streak without a homer was the second longest in her five-year career. Her season stats, as in every one of her seasons in Oklahoma, are nothing short of ridiculous: a .511 batting average, a .690 on-base percentage, and a 1.178 slugging percentage. It’s like she’s into a completely different sport, but as Gasso says, “It’s a relief, it’s a pride, it’s so many different emotions. What I’m most proud of Josie is that it’s always been a team effort. , “Let me find it,” or “Let me try to get to that record.” She’s not like that.”

While Gasso and I were talking on the left field line, Levi came up and put a lei around her neck and a wreath of flowers on her head. Gasso hugged him and said, “Doing it in front of this family – you can’t write a better script. And it wasn’t planned that way. I knew I owed her a ride.” [to Hawai’i]but it couldn’t have been written better. Full circle. Incredible. It couldn’t be the script.”

BANNERS HANGED from the backyard in the first park that couldn’t accommodate Jocelyn Alo’s talent:

Home Sweet Home Jocelyn Alo

Howula girl, welcome home

She returned on Wednesday, the day before the Rainbow Wahine Classic, and spoke with about 70 girls from the Ha’aheo girls’ softball program, as well as many of their parents. She stood on the dirt in the infield and unsuccessfully tried to hold back her tears as she told the girls, “This means a lot to me. I literally grew up here… I want you guys to dream about it too, and I want you guys to go further than I ever have.”

While the Ha’aheo players and her Sooners teammates camped for an hour on the field, Alo walked around the park to thank everyone who came. “Of course, this is a full circle moment,” she continued to say. Levy stood on the field, 100 yards from where five generations of his family had called home, and answered endless questions about his daughter’s chances of hitting a record home run or even seeing a field that makes it possible.

Gasso, who had never been to How’ul, said, “What I saw on that field was humility. You see a softball field that’s right in the middle of nowhere. There is no far fence. And what I will always remember is her emotion, just standing in this field in front of 70+ little kids saying, “My dream is coming true and I want you to be better than me.”

Jocelyn Alo, the greatest home run in NCAA softball history, stood on this field about 100 yards from the house she grew up in and 100 yards from the coconut trees that symbolize both beginning and end. She spoke of a talent that took her farther and farther away from this modest field and into the world of baseball stadiums, which also turned out to be too small to accommodate her. And in the end, the same talent that pushed her away ended up taking her back to where it all started.