Higher interest rates for longer.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

The data across the board, supported by countless industry reports, have all told a similar story: there is more demand for labor than labor supply.

The layoffs in the tech and social media bubble are being quickly absorbed by other companies, including in other industries, while layoffs and layoffs across all industries are near historic lows and unemployment insurance claims remain near historic lows lie. Wages have continued to rise; and for job hoppers, wages have skyrocketed as desperate companies are willing to pay to fill slots amid a gargantuan stack of job vacancies and massive job hopping as workers seek the narrower labor market in their favour.

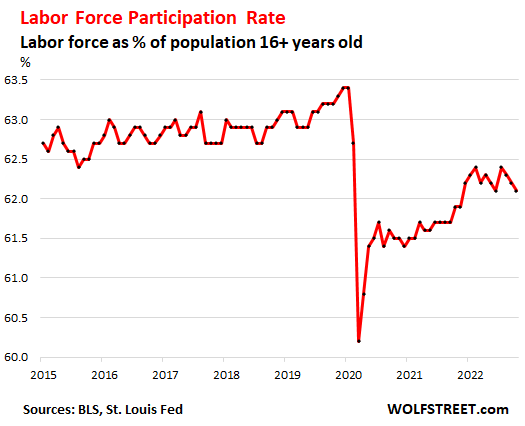

And today we have more of that with the Bureau of Labor Statistics job report. The labor force – people who are either in work or actively looking for work – remains the main problem: it has continued to fall and remains far below the pre-pandemic trend. This is the job offer.

Powell focused on the workforce in his speech two days ago. He pointed out that the Fed cannot increase labor supply and the Fed cannot increase labor; but the Fed can curb labor demand to bring some supply and demand into line to stem inflationary pressures that arise when companies pass on rising labor costs through price hikes. This is particularly a problem in services, which are now experiencing rampant inflation. And in many services, labor costs are a huge factor.

And this is happening everywhere now: companies that provide services are passing on their rising labor costs by raising their prices.

The Fed is now attempting to contain that demand for labor – in addition to demand for goods, services and investment – with the fastest rate hikes in four decades and the fastest QT on record.

But it’s not working yet. Consumer demand isn’t landing, and neither is the labor market. And inflationary pressures persist, particularly in “core services” where labor costs are a huge factor.

The labor force is not recovering back on trend.

The workers — people who are either in work or actively looking for work — fell by 186,000 people to 164.5 million in November, the third straight month of declines, roughly back to pre-pandemic levels but still surprisingly distant is below the pre-pandemic trend.

In other words, the labor force stopped growing after decades of growth as it recovered from the pandemic lows.

In his speech two days ago, Powell indicated there was a “shortage” in the labor force of about 3.5 million people compared to pre-pandemic trends, citing data from the Congressional Budget Office and the BLS. And I come up with roughly the same thing, based on BLS data and my own calculations: a “shortfall” between 3.5 million and 4 million:

Where does this deficiency come from?

The activity rate – the labor force as a percentage of the working-age population aged 16 and over – fell for the third straight month to 62.1%. This year it went backwards:

The employment rate in prime working age – people aged 25-54, eliminating the impact of boomers into retirement – also fell for the third straight month to 82.4%, but is close to pre-pandemic levels (83.1% in January 2020 and 2020). 83.0% in February 2020).

This shows that the biggest problem in the labor force is not the “prime working age” segment of the population, but the over 54 segment:

Powell on the “shortage” of labor.

In his speech, Powell discussed two sets of reasons responsible for most of this “shortage” of some 3.5 million people in the labor force: excessive retirements and slower growth in the working-age population.

“Excessive retirements”: 2 million of the 3.5 million shortfalls in the workforce. Excessive retirements are more retirements than would normally be expected based on aging alone. Powell was referring to recent research at his store.

According to Powell, what might have caused these excessive retirements:

- Health issues: ‘COVID has presented a particularly serious threat’ to the elderly.

- For older workers who lost their jobs during the mass layoffs, “the cost of finding a new job may have seemed particularly high given pandemic-related disruptions to the work environment and health concerns.

- “Gains in stock markets and rising house prices in the first two years of the pandemic contributed to wealth growth that likely enabled some people to take early retirement.”

And they don’t come out of retirement, according to Powell:

“The data so far does not suggest that excessive retirements are likely to be reduced as retirees return to the labor market. Older workers are still retiring at higher rates, and retirees do not appear to be returning to the labor market in sufficient numbers to meaningfully reduce the total number of excess retirees.”

Slower growth of working-age population: 1.5 million of the 3.5 million shortfall in the workforce. “The combination of a drop in net immigration and a spike in deaths during the pandemic is likely responsible for about 1.5 million missing workers,” he said.

The Fed cannot increase labor, but it can decrease labor demand.

The Fed’s tools “work primarily on demand,” Powell said. It’s not for the Fed to increase labor supply, he said. But it can reduce the demand for labor.

And we knew this: Higher interest rates make credit-financed consumption and investment more expensive for consumers and businesses, and they are being pushed back, thereby reducing demand for labour. Falling asset prices increase uncertainty among companies and new projects are being called back etc. further reducing demand for labour.

“In the short run, moderation in labor demand growth will be required to restore labor market balance,” he said. That was very hawkish.

And given today’s payrolls data, things got even more hawkish. So higher interest rates and more QT, because those are the tools at the Fed’s disposal to curb labor demand, which would dampen rising labor costs that companies are passing on to consumers via higher prices.

But the demand for labor did not cool: Aggressive attitudes pulled people out of self-employment.

The number of employed people who are not working has reached an all-time low. In November, it fell further to 6.0 million unemployed. There have only been three brief periods in the past five decades when the number of unemployed in the labor force has been so low.

What do employers do to fill their vacancies? They are aggressively hiring and offering higher wages to attract workers who already have jobs (which is fueling the current churn) and to attract workers who are self-employed…

The pull from self-employment to regular payslips is reflected in the gap between the growing number of workers on regular payrolls, as reported by employers, and the stagnant number of all workers, including the self-employed, consistent with the stagnating labor force, as reported by households.

The number of permanent employees increased by 263,000 in November from October and up by 816,000 in the last three months and by 1.9 million in the last 6 months to 153.5 million workers, an increase of 1.044 million from February 2020, according to the Employers Survey.

But the total number of workers, including the self-employed, fell by 138,000 in November and fell by 262,000 in the last three months to 158.5 million, which is still down 396,000 from February 2020, according to the household survey.

Both — payrolls and total workforce — are also well below pre-pandemic trends.

The stagnation of the total number of employed persons, as shown by the household survey, and the growth of regular wages and salaries, as shown by the establishment survey, show that employers’ efforts to fill their vacancies through higher wages and better benefits are moving into the employment sector for self-employment, while the total number of employed persons has not improved at all this year.

This situation where employers are struggling to fill vacancies – more labor demand than labor supply – is a good thing for workers. It has shifted the balance of power and it continues.

But now there is raging inflation, and that inflation is being fueled by a complex combination of factors, including massive amounts of money printing, interest rate cuts, and stimulus spending to produce the most overstimulated economy ever, and that money is still circulating outside, and it still creates demand for goods, services, and labor. And the Fed is now trying to contain that demand, including demand for labor, for much longer, with what Powell hinted at even higher interest rates.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it very much. Click on the beer and iced tea mug to learn how:

Would you like to be notified by email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

![]()