The newscast began like any other. Jorge Rendón, a veteran broadcaster with Ecuadorian state broadcaster TC Televisión in the busy port city of Guayaquil, went over the day's stories with his co-host.

Then, as the cameras rolled and the broadcast was broadcast live across the country, masked gunmen stormed the studio brandishing high-caliber rifles and grenades. Some of the crew members had to lie on the floor, others sat with their hands tied. Elsewhere in the building, shots were fired audibly on air before the broadcast was cut off.

“It was frightening, a moment of chaos and extreme tension,” Rendón tells the Financial Times. “They tried to make us raise our voices against the government, against the police and against the world. . . It was an afternoon of chaos.”

Shortly afterwards, a police squad recaptured the studio, arrested 13 intruders and freed the hostages. But similar harrowing scenes were playing out across the country, sparked by the Jan. 7 escape of jailed drug lord Adolfo “Fito” Macías from his cell in the nearby regional prison.

In the days since Fito – leader of one of the country's most prominent gangs, Los Choneros – went to prison, chaos has reigned in Ecuador. Over 158 prison guards and staff were taken hostage by inmates in seven prisons, vehicles and buildings were set on fire across the country, and at least 15 people, including police tenders, were murdered.

Journalists José Luis Calderón, Jorge Rendón and Stalin Baquerizo in front of the TC Televisión studios in Guayaquil, where they were held hostage by gang members © Portal

Journalists José Luis Calderón, Jorge Rendón and Stalin Baquerizo in front of the TC Televisión studios in Guayaquil, where they were held hostage by gang members © PortalPresident Daniel Noboa, a 36-year-old U.S.-educated scion of a banana empire who took office in November promising a tough line on crime, said Wednesday that Ecuador was in ” War”. Decree making them military targets. He also declared a nationwide two-month state of emergency, including nighttime curfews.

This week's harrowing events have brought home to many Ecuadorians the stark reality: that their country, once a relatively peaceful tourist destination nestled between larger and more violent neighbors, is on track to become the latest Latin American country to be plagued by the drug trade.

Criminals loot with impunity, corruption often goes unanswered and politicians are co-opted, threatened or worse – Fernando Villavicencio, a former investigative journalist and anti-corruption candidate for president, was assassinated last August.

According to the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (Flacso) in Quito, Ecuador's murder rate has risen nine-fold since 2017, when it was one of the lowest in the region, from five murders per 100,000 inhabitants to 46 last year, surpassing Mexico , Colombia and Brazil.

At the epicenter of the bloodshed are the country's overcrowded prisons, which have become bases for criminal gangs. Over 400 inmates have been murdered in the last four years, and riots and prison breakouts are commonplace.

The changing global demand for cocaine is one of the drivers of the crisis: markets in Europe, Asia and Brazil are growing, while consumption in the USA is declining. This has led to powerful cartels from Mexico penetrating Ecuador's barely monitored shipping ports.

Ecuador's descent into chaos has alarmed the region, particularly its neighbors Colombia and Peru. The latter declared a state of emergency on Tuesday on the northern border with Ecuador and stationed an unspecified number of troops there. Colombia, which has a porous border with Ecuador to the south, expressed concern about the security situation.

Ecuadorians are fleeing north in record numbers, with Panama reporting they are now the second largest nationality after Venezuelans to cross the Darién Gap – a dangerous jungle area © Luis Acosta/AFP/Getty Images

Ecuadorians are fleeing north in record numbers, with Panama reporting they are now the second largest nationality after Venezuelans to cross the Darién Gap – a dangerous jungle area © Luis Acosta/AFP/Getty ImagesThe crisis could also have dramatic effects beyond that. Ecuadorians are fleeing north in record numbers, with Panama reporting that they are now the second largest nationality after Venezuelans to cross the Darién Gap – a dangerous jungle area between Colombia and Panama that many migrants cross on their way to the US.

Border security is likely to be a hot topic in the US elections later this year. The Biden administration signaled it was paying attention; Brian Nichols, U.S. assistant secretary of state for Western Hemisphere affairs, condemned the violence and said Washington was “ready to provide assistance.” A high-level delegation, including the head of the US Southern Command, will visit Ecuador in the coming weeks.

Ecuadorians themselves are wondering how such a painful situation could have come about. “This is a country that has always lived in peace,” says Rendón. “Unfortunately, this peace has been shattered and a great responsibility lies with the various governments.”

The origins of Ecuador The crime wave can be traced in part to the policies of President Rafael Correa, a charismatic and combative left-wing nationalist who came to power in 2007 amid the so-called Pink Tide, which saw socialists rise to power across Latin America.

During a decade as president, Correa reduced the murder rate to historic lows through a mix of social spending that reduced poverty and increased policing and policies that allowed gangs to become legally recognized community groups by laying down their arms.

But at the same time he made Ecuadorian waters more attractive to smugglers by closing a US naval base in the port city of Manta in the name of national sovereignty. The privatization of ports along the Pacific also led to lax cargo security.

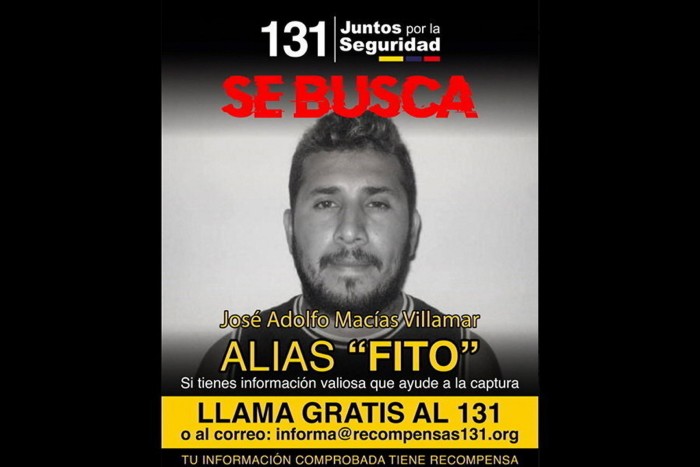

A wanted poster for Adolfo “Fito” Macías, leader of the Los Choneros gang © Ecuador's Interior Ministry/AP

A wanted poster for Adolfo “Fito” Macías, leader of the Los Choneros gang © Ecuador's Interior Ministry/AP“Correa did not believe that it was Ecuador's primary responsibility as a transit country to monitor the flow of drugs in and out of its borders,” said Will Freeman, a fellow in Latin American studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. “But that doesn’t mean that he is the only one who is partly to blame for the situation in Ecuador.”

When Lenín Moreno, Correa's former vice president, took office in 2017, he used a referendum to reform the state apparatus built by his former mentor by dismantling the Justice Ministry, but thereby losing control of the country's overcrowded prisons, he says Freeman.

Meanwhile, in Colombia, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) — a Marxist guerrilla group that had long monopolized drug trafficking routes in northern Ecuador — agreed to demobilize in 2016, leaving new territory for local gangs to take on.

Soldiers patrol the streets of Quito after President Daniel Noboa declared a two-month nationwide state of emergency © Karen Toro/Portal

Soldiers patrol the streets of Quito after President Daniel Noboa declared a two-month nationwide state of emergency © Karen Toro/PortalAnd when the Covid-19 pandemic hit Ecuador in early 2020, devastating the economy and public health of coastal port cities in particular, it left thousands of youth unemployed and created ideal recruits for gangs that grew in power and influence.

The membership of these gangs, including Los Choneros and Los Lobos, whose leader Fabricio Colón also escaped from prison this week, is now estimated by some experts to be as high as 50,000 people. With the agreements of the Mexican Sinaloa and Nuevo Jalisco cartels, these Ecuadorian gangs have made themselves an integral part of the global drug supply chain.

They have also diversified and make money from extortion, kidnapping and illegal mining. Crucially, they have begun to co-opt parts of the state, starting with prisons. Earlier this week, government spokesman Roberto Izurieta admitted that the prison system had “completely failed.”

As gangs have spread, security has deteriorated. Fernando Carrión, security expert at Flacso, says violence has become more brutal since 2017. “Over the last six years we have seen things become more and more violent, and today we see mutilations and bodies hanging from bridges.”

Moreno's successor, Guillermo Lasso, a self-proclaimed banking magnate, was also unable to stop the gangs' growing stranglehold when he took office in 2021. He dissolved Congress last May to prevent what he believed would be an impeachment trial was politically motivated and triggered early elections.

It was this election cycle – in which Villavicencio was shot dead by seven Colombian assassins as he left a campaign rally – that dramatically highlighted how far Ecuador had fallen into the gang trap.

Villavicencio had previously reported being threatened by drug trafficking groups, including the Choneros, although authorities have not yet linked them to the attack.

“Ecuador is virtually immersed in organized crime,” Villavicencio told the FT in an interview three months before his death, promising to “declare war” on the criminal industries if elected. “The war would combine direct combat on the streets, control of prisons and the isolation of all the bosses of the drug trafficking groups.”

Today it is Noboa who, as president, declared war on the gangs of Ecuador. In the decree signed Tuesday, he declared that the country was in an “internal armed conflict” and designated 22 gangs – including Los Choneros and Los Lobos – as terrorist organizations.

“We are at war and we cannot give in in the face of these terrorist groups,” he said in an interview with local media on Wednesday.

Noboa wants to hold a referendum that would allow the extradition of citizens accused of crimes abroad and the confiscation of suspects' assets, although the vote still requires approval from the country's Constitutional Court.

President Noboa has declared war on Ecuador's gangs © Carlos Silva/Ecuador Presidency/Portal

President Noboa has declared war on Ecuador's gangs © Carlos Silva/Ecuador Presidency/Portal“Ecuador is experiencing an unprecedented crisis, and the government’s response to it is also unprecedented,” said Sebastián Hurtado, head of Prófitas, a Quito-based political risk consultancy, referring to Noboa’s statement. “It offers Noboa a political opportunity to push through reforms and gain support for the referendum.”

The streets of Guayaquil have been quiet since Tuesday's violence. Many businesses remain closed, schools are closed and classes are taking place virtually. Trash continues to pile up as garbage collectors, like most public sector workers, are ordered to stay home. In the muggy city center, usually bustling with commerce, soldiers patrol outside municipal buildings.

Locals say tensions are high. “No one is shopping right now,” said Johanna Guanoluisa, one of the few market vendors who have set up shop in Guayaquil’s central Bahia district. “We are afraid because we know that if we open up we could be robbed.”

These fears are justified by sporadic outbreaks of violence across the country. In the Amazon city of Coca, arsonists set fire to a nightclub, killing two people and injuring nine. Five bomb attacks occurred in Quito on Wednesday, causing property damage but no deaths.

Turi prison in Cuenca. The country's overcrowded prisons have become bases for criminal gangs. More than 158 prison guards and staff are being held hostage by inmates in seven prisons © AFP via Getty Images

Turi prison in Cuenca. The country's overcrowded prisons have become bases for criminal gangs. More than 158 prison guards and staff are being held hostage by inmates in seven prisons © AFP via Getty ImagesUnions representing prison workers, more than 158 of whom remain hostage in their own prisons, have criticized the government for failing to provide information about their welfare, while unverified videos of guards appearing to be tortured circulate on social media become.

Rear Admiral Jaime Vela, the armed forces commander, told reporters on Wednesday evening that none of the hostages had been killed and that 329 people, mostly gang members, had been arrested since the state of emergency began on Monday.

Meanwhile, Noboa's tough rhetoric, reminiscent of El Salvador's popular strongman Nayib Bukele – whose crackdown on gangs has gained support across Latin America despite concerns about authoritarianism – appears to be resonating with Ecuadorians weary of their country's insecurity.

Noboa's plan to wage war against the “terrorists” is “the only way to get rid of all this crime,” said Mariuxi Paredes, a shopkeeper in downtown Guayaquil. “A dead dog doesn’t bite.”

Additional reporting by Christine Murray in Mexico City