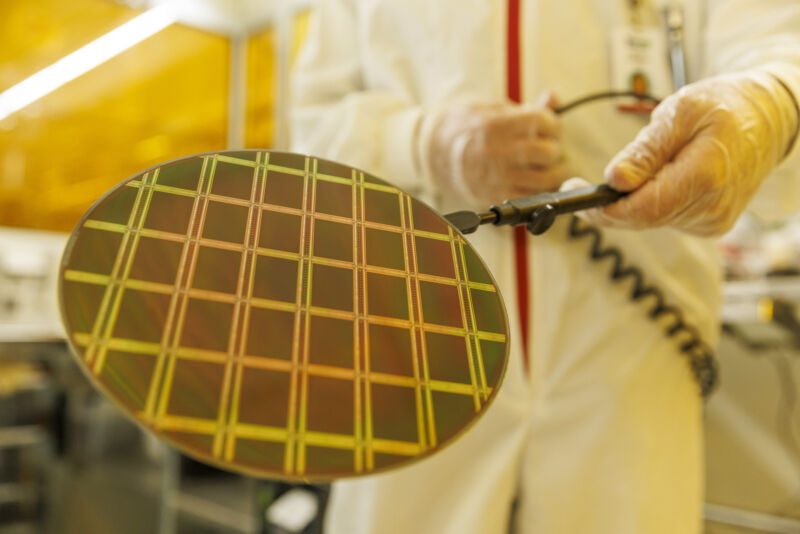

Enlarge / Technicians inspect a wafer during clean room testing at Tower Semiconductor Ltd. in Migdal HaEmek, Israel.

Bloomberg | Getty Images

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine threatens to put additional pressure on chip production as cuts in supplies of rare gases critical to the manufacturing process exacerbate pandemic-related disruptions.

Ukraine supplies about 50 percent of the world’s neon, a by-product of the Russian steel industry that is refined in the former Soviet republic and indispensable in chip production, analysts say.

Manufacturers have already suffered from component shortages, supply delays and rising material costs, and companies that rely on chips, such as car makers, have experienced production delays as a result.

Many companies, including U.S. manufacturers Applied Materials and Intel, have said restrictions will continue through 2023. Demand for raw materials is also expected to rise by more than a third in the next four years as companies such as the world’s largest contract chipmaker Taiwan Semiconductor will ramp up production, consulting firm Techcet said.

“We are in big trouble. We don’t have rare gases to sell,” said Tsuneo Date, manager of Daito Medical Gas, a pressurized gas trader north of Tokyo.

When Russia invaded Crimea in 2014, neon prices jumped by at least 600 percent. Companies say they can draw on reserves, but the rush to find suppliers outside Eastern Europe is causing shortages and rising prices not only for neon, but also for other industrial gases such as xenon and krypton.

Forty percent of the world’s supply of krypton comes from Ukraine. The price of gas, which is used in semiconductor manufacturing, rose from 200-300 yen ($1.73-$2.59) per liter to nearly 1,000 yen ($8.64) per liter by the end of January, Date said.

He added that prices had been rising before the war due to disruptions in the supply chain, but said “the Russian invasion of Ukraine is making things worse” and that he had recently been forced to turn down orders from new customers.

Companies in the supply chain have developed new technologies, diversified neon gas sources and increased stocks since the Crimean crisis, providing some breathing space. In 2016, multinational industrial gas supplier Linde invested $250 million in a neon plant in Texas as customers sought to diversify supplies.

Advertising

Yoshiki Koizumi, president of the trade publication Gas Review, said: “Supplies of neon, xenon and krypton are definitely becoming more limited because chipmakers and trading houses are placing more orders in anticipation that they won’t be able to get as much in the future. as they wish.”

Ke Kuan-han, a semiconductor analyst at consultancy Techcet, said the reaction was “immediate,” adding, “I’ve heard that spot prices have jumped several times over.”

Neon prices are negotiated on the basis of individual long-term contracts with processors and microchip manufacturers, and part of the gas is also sold on the spot market. Several chipmakers and major gas companies in Japan declined to comment on current spot prices.

He added that mitigation efforts have given companies some room to deal with disruptions in the short term, and they hope the conflict does not drag on.

A Deutsche Bank research note said industry inventory levels typically hold for three to four weeks.

Kim Yong-woo, a technical analyst at SK Securities in Seoul, said that while South Korean companies such as Samsung and SK Hynix could find replacements for some gases, “the supply shortage could be severe for krypton and neon.”

Gas mixtures containing neon are used to power lasers for etching patterns in semiconductors. Giving up Ukraine is difficult because it needs to be purified to 99.99% purity, a complex process that only a few companies around the world are capable of, including those based in the Ukrainian port of Odessa.

Highlighting the problems, the White House warned semiconductor makers to diversify their supply chains in the wake of the Russian invasion. ASML, a Dutch company that makes machines for making chips, said it was looking for sources of neon outside of Ukraine.

Japanese chip makers Renesas and Rohm said they have either found supplies in other markets such as China or stockpiled neon.

Samsung and SK Hynix, the world’s two largest memory chip makers, “have factories in China, so they won’t have a problem getting gases there to make chips,” Kim said. The companies said the impact of the war on their chip sales would be minimal in the short term.

But in a note published shortly before the invasion, TrendForce analysts warned that even if alternative sources were provided, “certification of the product will take several months or even more than half a year,” leading to a “shortage.”

They warned that “the automotive industry, which requires a large number of power management chips and power semiconductors, will face a new wave of material shortages.”

Akira Minamikawa of research firm Omdia said that all products using the chips would be affected because only the most advanced semiconductors do not require neon in their production. “It’s not like neon is used in chips for cars, but not for smartphones.”

Reporting by Anthony Slodkowski and Eri Sugiura in Tokyo, Song Jong-ah and Edward White in Seoul and Eleanor Olcott in London

© 2022 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Redistribution, copying or modification in any way is prohibited.