This week, the COP28 climate summit ended with a text calling on nations to abandon fossil fuels to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. For many it is a historic event. Firstly, because it is the first time in three decades of agreements that a direct reference to these fuels, which are mainly responsible for the climate crisis, is included. The elephant in the room has been highlighted, as expressed by Manuel Planelles, this newspaper's envoy to the Dubai summit. But the goal is also significant for another reason: because it will be difficult to achieve it without falling into fine-print excuses.

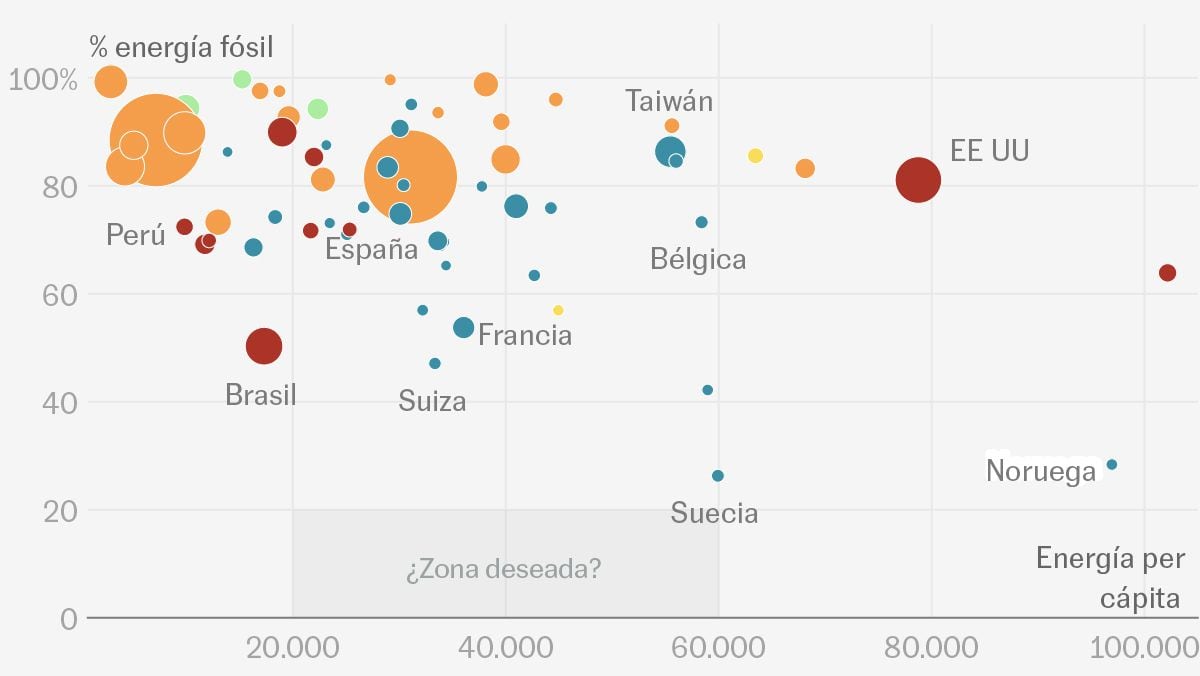

Look at the graphic. The world's fossil fuel consumption is still enormous – accounting for 82% of our total energy – and continues to grow. According to Our World in Data, coal use has stabilized over the past decade, but oil and gas use has continued to increase.

What are the forecasts for the future? The International Energy Agency forecasts say we are close to peak – the moment of highest consumption in history – but have not yet passed it: “We are on track to see the peak of all fossil fuels before 2030.” . If this is met, there will be a period of two decades to bring the curve down.

This is something no major country has yet achieved.

But it is very interesting to observe the differences between nations. To that end, I created this other graph with Borja Andrino that crosses two key variables: (1) the consumption of energy of any kind per person and (2) the percentage of that energy obtained from fossil fuels.

The graphic shows the variety of situations. At one extreme is Bangladesh, which uses little energy but gets it entirely from fossil fuels. Another is the United States, which is one of the countries that consume the most energy, and 80% of it is fossil fuels. Where can we find more positive examples? Brazil (still) uses little energy and only half is fossil fuel (it uses a lot of hydropower). And then there are the Nordic Europeans, who have reduced fossil fuel use to just 26% in the case of Sweden.

We can use the same graph to see the trajectory that some countries have taken over the years, speculating about the path they need to take to reach the zero emissions target in 2050. For example, in the last 10 years, both China and the United States have begun to reduce the proportion of fossil fuels in their mix. In the American case, this was achieved while reducing overall energy consumption; in the Chinese as they increased it at the pace of their economy.

Finally, we focused on the development of some European countries. Here the goal is closer (moderate consumption and no fossil fuels).

One success is Denmark, which has significantly reduced the share of oil, gas and coal in energy consumption since 1995 to date, reducing it from 98% to 57%.

France reduced the share of fossil fuels from 88% to 55% between 1975 and 1995 through the use of its nuclear power plants (whose contribution was almost 40%). What they have then done over the last 20 years is to reduce overall consumption, also reduce nuclear energy and increase renewable energy.

And Spain? I was impressed by the peak of energy consumption during the bubble years in 2005. After that, there was an improvement, although not spectacular: we have slightly reduced total energy consumption and also the weight of fossil fuels, although it is still 70%.

Other stories

🍿 Most viewed on Netflix…

The streaming company is publishing increasingly detailed information about its titles. We can see, for example, that last week the film “Leave the World Behind” was the most viewed, with 41 million views (myself included; I really liked it). They also have a historical ranking of the best releases, by number of views within the first 90 days (I saw four of the ten; none of them wowed me). In addition to their biggest hits numbers, they've now added a database with information on 18,000 tracks.

🎂 Was your child born in the same month as you?

A study has just been published that says it's not just a coincidence. If your mother was born in spring or any other time of year, chances are you were born too. That is, there is a connection between the birth month of the parents and that of the children, which tends to be (slightly) more likely to fall in the same month or season than chance would suggest.

Using recent data from France and Spain, they find that the number of mothers sharing the birth month with their children is 2 to 3% higher than expected. They also found the same agreement in the date of birth of married couples and between different children of a couple.

What do you think is the reason? The explanation would be essentially social, as one of the work's authors explained to me via email: Adela Recio Alcaide: “Our lifestyle makes us more likely to become pregnant at some times than at others; and in general, our way of life and that of our relatives are similar.” For example, it has been observed that women with higher education give birth more often in the spring (because they become pregnant more often during the summer holidays). And since you are more likely to study if your parents have studied, the two are connected: in a family with more degrees, there will be a (small) tendency to be born more often in the spring.

🤖 ChatGPT among the scientists of the year 2023

Nature magazine has chosen a non-human being for its list for the first time: “The artificial intelligence system has been a force in 2023, for better or worse,” it says. Daniel Mediavilla summarizes the other chosen ones, including Ilya Sutskever, chief scientist and co-founder of OpenAI, the organization that founded ChatGPT.

As the magazine says, Sutskever “has played a key role in the development of AI systems that are beginning to transform society.” The text tells a story that, in retrospect, sounds prescient. As a teenager, Sutskever turned to the University of Toronto, knocked on the door of Geoffrey Hinton – a pioneer of neural networks – and asked for a job: “He told me that he fries potatoes in the summer to make money, and that “I would rather do work.” For me, I do artificial intelligence,” says Hinton. The professor adds another detail about his student: “It’s not just his intelligence that sets him apart,” he clarifies. “It’s also the urgency with which he does things.”

You help me? Forward this newsletter to anyone you want. If you are not yet subscribed, sign up here. It is an exclusive newsletter for EL PAÍS subscribers, but anyone can receive it for a trial month. You can also follow me on Twitter at @kikollanor write to me with tips or comments at [email protected].